As tens of thousands return to the streets for the first national Palestine march of 2026, this movement refuses to be sidelined or silenced, says PETER LEARY

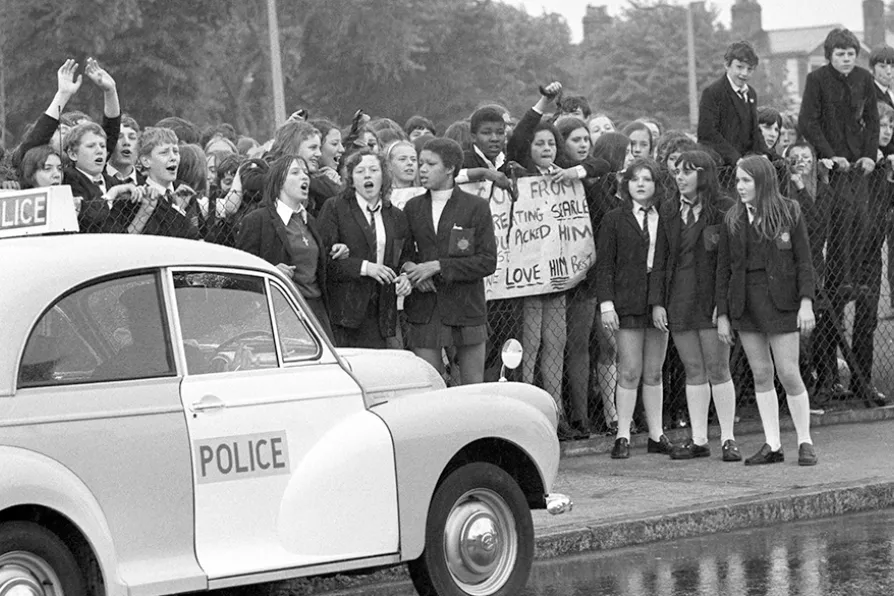

FIGHTING FOR THEIR RIGHTS: Pupils of the Sir John Cass Foundation and Red Coat Church of England Secondary School demand the reinstatement of Christopher Searle

FIGHTING FOR THEIR RIGHTS: Pupils of the Sir John Cass Foundation and Red Coat Church of England Secondary School demand the reinstatement of Christopher Searle

THIS month marks 50 years since Chris Searle, a young English teacher at the Sir John Cass school in London’s East End, hit the headlines after being sacked for encouraging his pupils to write poetry about their own lives and neighbourhoods.

The school’s pupils came from a variety of cultural backgrounds, black and white, virtually all working class and very often poor. From the word go, these children had been treated as incapable of going far in life, as barely educable and told repeatedly that they were thick, so any hopes or ambitions they might have had for their lives was stymied before they had a chance.

Searle refused to accept this view, knew that these children had more to offer and could be enormously creative if they were given the chance.

‘Chance encounters are what keep us going,’ says novelist Haruki Murakami. In Amy, a chance encounter gives fresh perspective to memories of angst, hedonism and a charismatic teenage rebel.

The bard mourns the loss of comrades and troubadours, and looks for consolation with Black Country Jess

We face austerity, privatisation, and toxic influence. But we are growing, and cannot be beaten