In his second round-up, EWAN CAMERON picks excellent solo shows that deal with Scottishness, Englishness and race as highlights

Error message

An error occurred while searching, try again later.MATTHEW SHARPE recommends the essays of a Renaissance politician that instruct and unnerve after 400 years

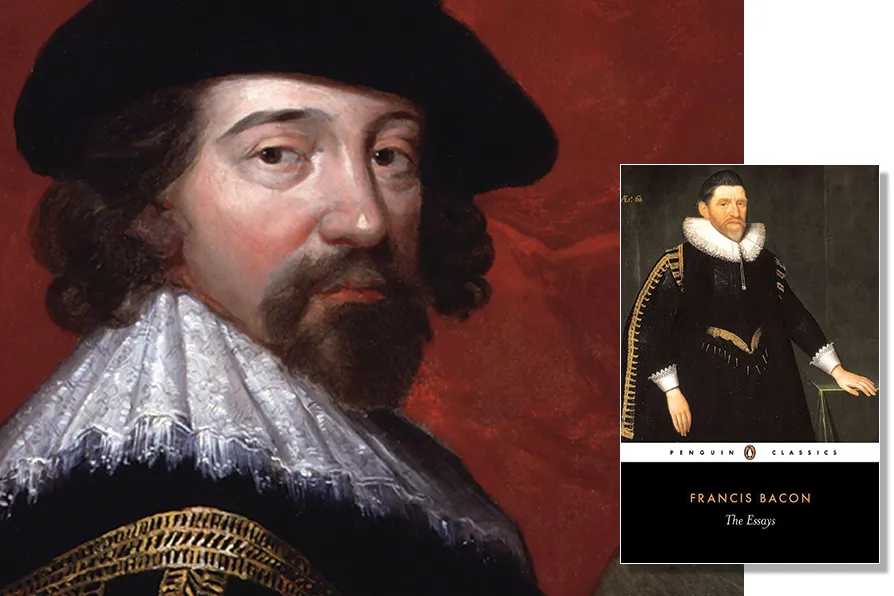

Portrait of Francis Bacon, Viscount St Alban, by John Vanderbank, c1731, after a portrait by an unknown artist c1618 [Pic: Public Domain]

Portrait of Francis Bacon, Viscount St Alban, by John Vanderbank, c1731, after a portrait by an unknown artist c1618 [Pic: Public Domain]

The Essays

Francis Bacon, Penguin Classics, £12.99

IT’S 400 years since the publication of the complete edition of British philosopher Francis Bacon’s Essays. Not without pride, Bacon (1561-1626) muses in the preface that his little book’s Latin version might “last, as long as books last.” The Essays have, in fact, never been out of print since 1625.

A renaissance man, Bacon was the son of Queen Elizabeth’s Lord Chancellor. From early on, he was drawn into a political life at the court. He eventually rose to the lord chancellorship himself under King James, before falling from grace in disputed circumstances in 1621.

The Essays address social, moral and political subjects. They first appeared in 1597, (as a collection of just 10), expanding to an edition of 38 essays in 1612. Then, in 1625, the final edition of 58 essays was published.

What makes Bacon’s Essays so continually incisive is that, alongside Machiavelli (whom he admired), Bacon is among the first and most discerning authors to unsentimentally explore the darker sides of human nature.

When it comes to the “civil knowledge” Bacon proffers in essays like Of Negotiating (a Renaissance take on the art of the deal), his concerns are primarily those of the courts, aristocrats and monarchs of his day. Several of these essays, on the pageantry and manners of the elites, are now (understandably) dated.

But others can be read as discerning studies in what we call “leadership theory.” They address the psychological and ethical challenges people in leadership face, if they are not to misuse their power — or be misused by others.

The problem is that good intentions may not get far in public life, Bacon counsels, if a person is not awake to the ways in which such intentions can be misled and abused. For Bacon, we have to understand the wiles of the “tyrannical and unjust” if we are not to fall prey to them, over and over:

“For it is not possible to join serpentine wisdom with the columbine innocency, except men know exactly all the conditions of the serpent; his baseness and going upon his belly, his volubility and lubricity, his envy and sting, and the rest; that is, all forms and natures of evil.”

This is why Bacon’s Essays include examinations of different kinds of deceit and concealment, itemising in fine detail the ruses “movers and shakers” use to promote themselves, often at the expense of the wider good.

“Cunning men,” Bacon says nicely, “are like haberdashers of small wares.” If people with more generous intentions do not know how to recognise these “wares,” such men can cause great harm to businesses, workplaces, even entire nations.

Bacon warns us: “Nothing doth more hurt in a state, than that cunning men pass for wise.” To be forewarned, by contrast, is to be nobody’s fool.

There are essays of great lyrical beauty like Of Adversity or, indeed Of Beauty. These can almost be savored for their poetry alone.

However, there are other essays which Bacon clearly wants us to read closely, chewing over and applying the observations and advice they give us for our professional or public careers. Alongside Of Cunning, Baconian essays almost worthy of a criminologist or forensic psychologist include Of Boldness, Of Ambition, Of Envy, Of Revenge, and Of Vainglory.

Bacon also includes insightful political essays like On Seditions and Troubles. This longer piece identifies the signs and steps whereby states collapse, when they fail to defend their basic norms and institutions against seditious adventurers and factions. Signs of trouble include: “Libels and licentious discourses against the state, when they are frequent and open; and in like sort, false news often running up and down…”

With false news rampant today in ways Bacon could scarcely have imagined, the reader of 2025 can be struck by the insight and foresight of his “civil and moral counsels.”

Four hundred years later, the philosophical Lord Chancellor’s Essays still instruct and unnerve.

Matthew Sharpe is associate professor in philosophy at the Australian Catholic University.

This is an abridged version of an article republished from TheConversation.com under a Creative Commons licence.

![]()