RITA DI SANTO draws attention to a new film that features Ken Loach and Jeremy Corbyn, and their personal experience of media misrepresentation

Error message

An error occurred while searching, try again later.GAVIN O’TOOLE welcomes the reissue of a seminal work of revolutionary theory that have genuine relevance in the current context

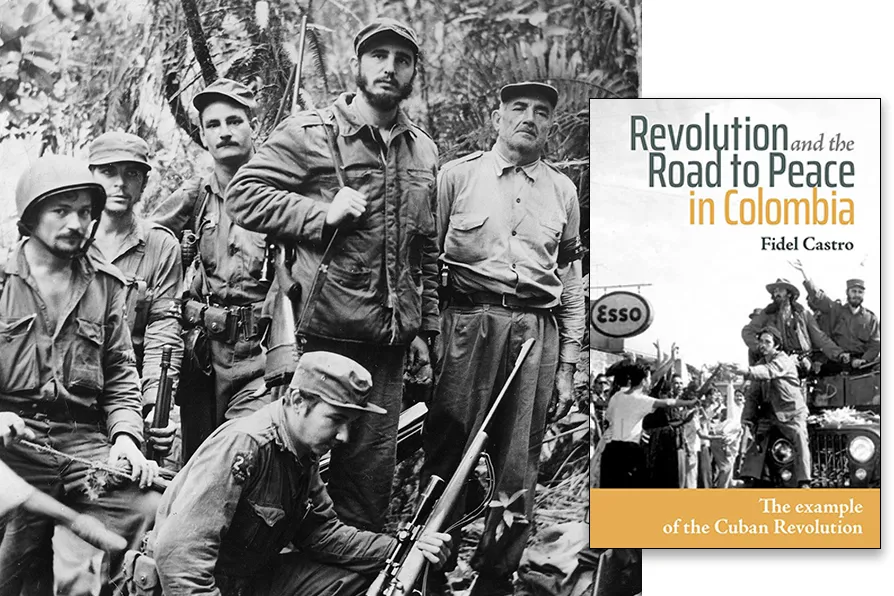

Fidel Castro in the Sierra Maestra, December 1956. From left: Guillermo García, "Che" Guevara, Universo Sanchez, Raul Castro (kneeling) Fidel Castro and Crescentio Perez [Pic: Public Domain]

Fidel Castro in the Sierra Maestra, December 1956. From left: Guillermo García, "Che" Guevara, Universo Sanchez, Raul Castro (kneeling) Fidel Castro and Crescentio Perez [Pic: Public Domain]

Revolution and the Road to Peace in Colombia: The Example of the Cuban Revolution

Fidel Castro, Pathfinder, £12.23

SCRATCH away the local, ethnic and religious tensions of the world’s hotspots and, from Gaza to Syria to Kashmir to Sudan to Congo to Ukraine, you will find the nefarious hand of imperialism moving the chess pieces in its favour.

The same has long been true of Latin America, if more obviously so, where enduring conflicts that have stained the land red have been stoked by the alliance between local and Western capital employing militaries as proxies to remove obstacles to exploitation.

The imperial game of chess goes beyond military conflict, however, and reaches deep into the realm of politics.

It is precisely the confrontation under way right now between Washington and Brazil, as Donald Trump uses the heft of his country’s economy to bend Brasilia to his political will in support of local conservative forces that are in the pocket of America.

Given this, it cannot be overstated how internationalism offers the best hope of resistance to the violence capitalism visits upon the global South through the militarisation it is fostering anew in the global North.

Understood in the long duree, the war against imperialism in Latin America has been under way since at least 1910, with the Mexican Revolution — we have already passed its century and historians of the left will eventually be called upon to name this period.

They might choose to call it the “Cuban interregnum” because one nation more than any other has been consistent in its resistance to imperialism and has brought it into a praxis that builds upon a wealth of Latin American theory, from Mella and Mariategui to Sandino and Haya de la Torre.

A good introductory insight into Cuban anti-imperialism and the internationalism upon which it is based can be gained from Pathfinder’s latest reprint of work by Fidel Castro, whose contemplations take on genuine relevance in the current context.

It is easy to dismiss the reproduction of Castro’s often rambling speeches as an act of devotion to a socialist saint by an ageing cadre of unreconstructed Marxists who retain faith in a revolution that young people today are simply unfamiliar with.

But that is precisely why it is necessary, because since the neoliberal turn of the 1990s the triumphant global right has systematically been dismantling the legacy of the Cuban transformation in the minds of younger generations.

This slow erasure of socialist discourse, theory and, indeed, history itself, debilitates today’s left and so, in turn, demands that we retell them with a new conviction.

It goes without saying that the Cuban Revolution remains one of the most important events of the 20th century for demonstrating how the people of a small, weak vassal of US capitalism within spitting distance of the beast were able to throw off their shackles.

They did so primarily not with weapons of war, but using ideas, unity and solidarity, the ideological glue of which was an internationalism that would distinguish revolutionary Cuba from its peers and guarantee its immortality.

As Castro himself stated during the guerilla war: “Our apostle Jose Marti said that what matters is not the number of weapons in hand but the number of stars on one’s forehead … Victory in war depends on a minimum of weapons and a maximum of moral values.”

Revolution and the Road to Peace in Colombia offers a series of reflections by Castro and commentaries on what he said. The main theme is the political lessons he drew from the Cuban revolutionary leadership’s efforts to bring an end to the lengthy civil war in Colombia.

The origins of the conflict between a Colombian state enslaved by Washington and revolutionary guerillas lay in the internecine fighting of the capitalist ruling class, leading ultimately to the victory of conservatives whose motive was to rape peasant land for profit.

The work presented here offers insights into Castro’s understanding of Cuba’s own revolutionary struggle and how he sought to apply this to the peace talks in which his country played the critically important role.

A recurrent theme is the notion of proletarian internationalism and the ethics associated with this that guided Cuba’s revolutionaries from the outset, greatly aiding how they mobilised working people to their cause by fostering class consciousness.

In their preface, Roger Calero and Steve Clark argue that the example of proletarian internationalism and ethics set by Cuba’s rebel army for working people across the world stood in stark contrast to that of the FARC and other guerilla organisations in Colombia.

In this vein, the book opens with a 1958 speech by Castro broadcast from the Sierra Maestra during the revolutionary war in which he places at the heart of the guerilla ethic the rebels’ humane treatment of Batista’s soldiers who surrendered or were captured.

The main bone of contention between Castro and the FARC leadership, particularly Manuel Marulanda, who had also been a leader of the Communist Party of Colombia until the FARC’s breakaway in 1993, was the nature of the struggle itself.

Castro pointed to the relationship between the Colombian CP and the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, which was why it “never had the goal of taking power” but was from its outset “a resistance front.”

The Cuban leader’s conviction was that a genuine revolution was possible only through the massive involvement of working people, independent of bourgeois political parties, in the direct pursuit of gaining power to undertake a revolutionary transformation.

Hence Cuba’s growing guerilla army comprised overwhelmingly of exploited workers and peasants coming together in the effort to defeat a dictatorship backed by Washington — and thence to build a new society.

Cubans who had fought on the front line then mobilised in every sector in voluntary brigades that took education, literacy, housing, land reform and medicine to all corners of society.

As Calero and Clark note: “Faced with mounting aggression from foreign and domestic capitalists, they expropriated US-owned factories and plantations and then the properties of Cuban exploiters. From their very first days in power, they extended solidarity to those fighting imperialist oppression and exploitation around the world.”

Among contributions to this collection of speeches and essays is a 2023 talk presented in Havana by Mary Alice Waters, a leader of the Socialist Workers Party in the US, in which she underlines the principled consistency over decades of Castro’s position, and in particular the key theme of this book: proletarian internationalism.

“Proletarian internationalism,” Waters says, “is not only a foreign policy, it is an expression of the revolution itself” and “if Fidel belongs first to the working people of Cuba, he also belongs to oppressed and exploited peoples the world over.”

She explores how, under Castro’s leadership, the working people of Cuba showed what proletarian internationalism meant in practice — from Latin America and the Caribbean, to Africa, Asia, North America and Europe.

She highlights Cuba’s noble internationalist mission in 1975 to aid the people of Angola and Namibia facing the aggression of the racist, apartheid regime of South Africa and its enablers in Washington.

What is considered Cuba’s greatest act of international solidarity on the battlefield and its substantial support for national liberation struggles against imperialism in every region of the world have, however, arguably been eclipsed by its non-military, humanitarian programmes and solidarity with progressive governments.

Given the array of imperialist forces that have been thrown against it — an unrelenting illegal blockade, a military invasion, countless acts of sabotage, assassination attempts and a global war of poisonous propaganda — it is this internationalism that explains the survival of the Cuban Revolution.

As the world’s most influential non-aligned country with an unprecedented international network of friendships, Cuba’s ability to withstand US aggression to this day demonstrates the concrete relevance of solidarity as the left’s most important weapon against imperialism.

And that is why a book about a revolution that triumphed 66 years ago, containing the thoughts of a leader who died aged 90 in 2016, should not just be of interest to nostalgic veterans dreaming of the triumph they never had — but should be required reading across the entire left as a living, breathing inspiration of what remains possible.