As tens of thousands return to the streets for the first national Palestine march of 2026, this movement refuses to be sidelined or silenced, says PETER LEARY

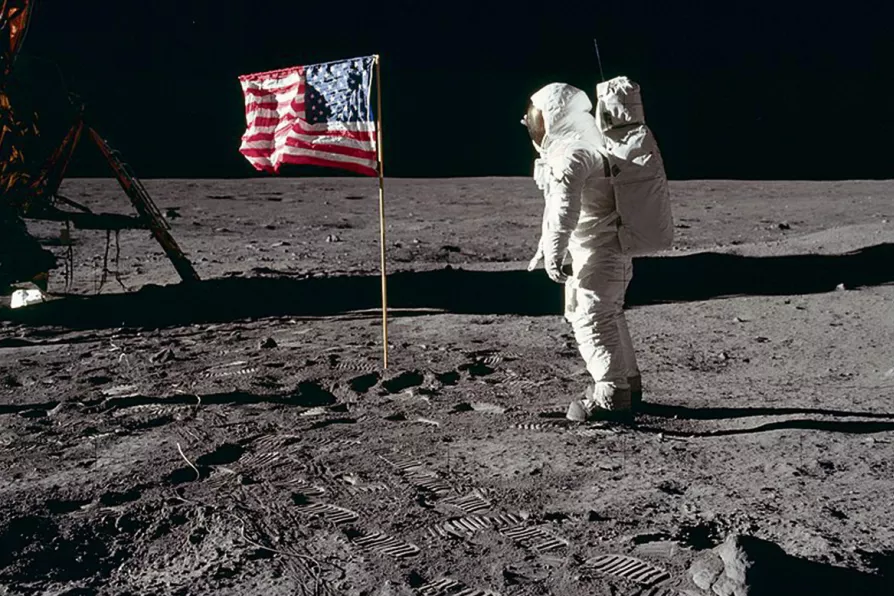

Buzz Aldrin, lunar module pilot of the first lunar landing mission Apollo 11 on July 20 1969

[Nasa/Neil A Armstrong/Creative Commons]

Buzz Aldrin, lunar module pilot of the first lunar landing mission Apollo 11 on July 20 1969

[Nasa/Neil A Armstrong/Creative Commons]

IN early June 2019, a fake video of Mark Zuckerberg, the CEO of Facebook, began to circulate around the social media platform Instagram. In it, he appeared to thank a shadowy organisation called “Spectre” for helping him manipulate people into willingly divulging their personal information to him.

The video, which is still available to watch on YouTube, looks authentic, but was in fact generated by an algorithm that is able to mimic human voices and facial appearances. Worryingly, other algorithms exist that can do the task even more convincingly.

An international team of scientists, working with Adobe — the company that is responsible for Photoshop, commonly used to create doctored images — have created software that can alter the words that people say in a video of them speaking.

If true, the photo’s history is a damning indictment of the systematic exploitation of non-Western journalists by Western media organisations – a pattern that persists today, posit KATE CANTRELL and ALISON BEDFORD

SCOTT ALSWORTH searches for something – anything – worth recommending from the year’s releases

ELIZABETH SHORT recommends a bracing study of energy intensive AI and the race of such technology towards war profits