RITA DI SANTO draws attention to a new film that features Ken Loach and Jeremy Corbyn, and their personal experience of media misrepresentation

HEIDI NORMAN welcomes a new history of the Aboriginal resistance to white settlers in New South Wales

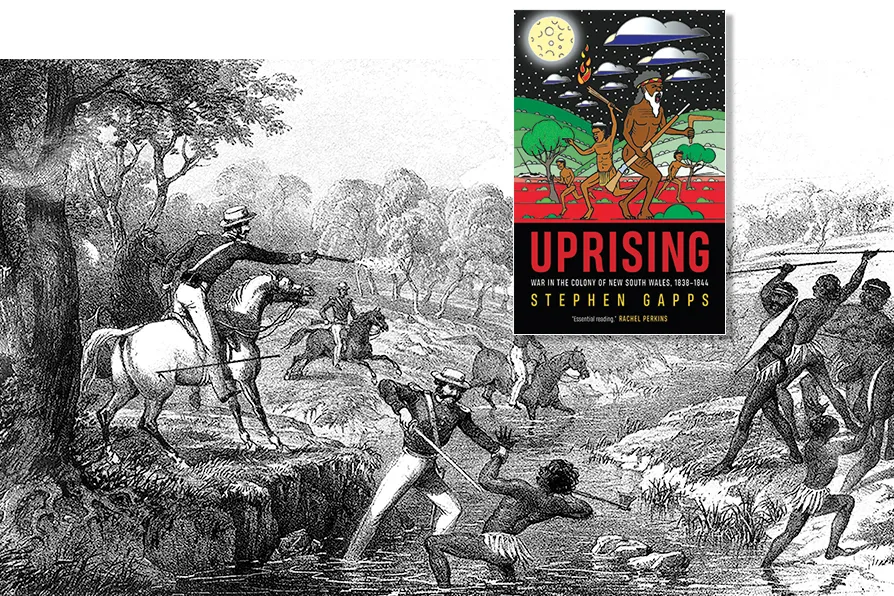

Mounted police engaging Indigenous Australians during the Slaughterhouse Creek clash of 1838 / Pic: W.Walton after Louisa and Godfrey Charles Mundy/CC

Mounted police engaging Indigenous Australians during the Slaughterhouse Creek clash of 1838 / Pic: W.Walton after Louisa and Godfrey Charles Mundy/CC

Uprising: War in the Colony of New South Wales, 1838 - 1844

Stephen Gapps

New South Publishing, £17.99

IN THE 56 years since eminent anthropologist WEH Stanner challenged historians to address the curious “silence” around the recent Aboriginal past, an enormous body of research by historians and others working in the field has transformed the discipline.

Historian Stephen Gapps’s latest book, Uprising: War in the Colony of New South Wales, 1838–1844, describes a co-ordinated Aboriginal military front across more than 20 different Aboriginal nations and language groups. The front extended for thousands of kilometres, from Port Phillip in the south to Moreton Bay in the north.

Over this extended arc, war raged for several years from the late 1830s.

This history is revealed through detailed research of settler archives: reports, news stories, and survivor testimony. Gapps establishes that organised and co-ordinated bands of warriors waged a successful campaign across multiple sites, which forced the soldiers, shepherds and settlers to retreat. He calls this the “uprising” and those who waged it “warriors.”

The warriors deployed a range of tactics to terrorise the invaders, forcing many to flee their holdings. By the mid 1840s, however, the squatters became militarised and more accustomed to the warriors’ style of warfare. The parliament grew concerned to protect grazing profits. Gapps notes that the colonial population had doubled, from nearly 98,000 in 1838 to 181,556 in 1845. Horse, sheep and cattle numbers also exploded. The rush to claim land beyond the “limits of location” meant the warriors were increasingly outnumbered.

As I read Uprising, I thought about my Aboriginal family. My great-great-great-grandmother, Mary Anne Tidswell, was born in 1836, on the eve of the swarming of her country by sheep and soldiers and the uprising of her people. By the time her second daughter was born in 1864 – my great-great-grandmother, Emma Dingwell – a new world had descended on the occupied plains of north-western New South Wales.

Gapps’s account differs from these earlier studies of Aboriginal resistance primarily because he considers the uprising in relation to military history. Rather than treating colonial violence as the predominant organising dynamic, he focuses on Aboriginal tactics and strategies, and finds a distinct pattern of warfare. His innovative interpretation contests most of the military-focused histories of resistance.

Scholars have usually insisted that Indigenous societies, where people are organised according to responsibilities to place and have a non-hierarchical relation to one another, mitigate against organised military campaigns. Uprising presents evidence that, in the period between 1838–44, and beyond in far western New South Wales, Aboriginal groups formed a co-ordinated resistance.

Rather than a narrative of “military weakness” and inability to adapt traditional tactics to war against the colonisers, Gapps proposes that 20 different groups “made a defiant stand against the push into their lands.” He documents an extensive resistance that benefited from networks of communication and shared strategies to repel the invaders.

He establishes, for example, that the warriors were using axe heads well before the invaders arrived. He argues this is explained by already extensive networks, which were used to exchange resources, observations and tactics. He also establishes that the warriors used firearms and stockpiled weapons.

Gapps questions accepted accounts that the use of horses and rifles proved critical to overwhelming Aboriginal resistance. Instead, he shows that the tactics deployed by Aboriginal warriors were effective along the rivers, creeks and gullies – conditions that did not necessarily lend themselves to the style of war the British were conditioned to fight.

The warriors’ deep knowledge of the country supported their military tactics. They would draw the soldiers into ravines rather than fighting on open plains, and they separated larger groups of soldiers into smaller, more vulnerable groups before setting upon them.

All these accounts are vividly painted and drawn from archival sources.

Gapps identifies two leading strategies in the warrior uprising. One was to destroy the squatters’ property and kill their stock, denying them thousands of pounds worth of cattle and sheep. As Gapps details, some squatters were “ruined” and “up and left.” Historians have attributed the squatting bust of the 1840s to drought and over-investment. Gapps offers a counter explanation: the warriors were a significant undermining factor.

The other tactic the warriors deployed was terror. Resistance fighters terrorised the invaders “forcing convict shepherds to cower in their hunts, swim rivers and flee for their lives, refuse to work for their overseer, destroy their firearms and go insane in the bush.”

The warriors could number as many as 1,000 in one camp alone. Not only did they successfully wage a war of terror; they sustained their camps and fighters on a diet of the invaders’ livestock. Soldiers travelling in the warriors’ wake came upon one camp that was strewn with the bones of sheep and cattle.

Gapps describes the uprising of 1838–44 as a “highpoint of resistance to the colonisers.” After this period, the colonisers deployed new strategies to overwhelm the resistance. Gapps reminds us of the terrible consequences of the deployment of the Queensland Native Mounted Police, established in 1849.

Further west, as the moving frontier and patterns of settlement encountered the Barkandji people, the Barka (Darling) river became a war zone. Warriors burnt down the invaders’ infrastructure and left stockyards in ruins. Gapps records that, in December 1845, Major Thomas Mitchell saw this as “humiliating proof that the white man had given way.”

Gapps’s research is extensive. The bibliography and references make up nearly a quarter of the book. The richness of the archival evidence is impressive.

The significance of the uprising of 1838–44 has been poorly understood. Australian military history is still unsure how to represent the frontier wars. There are no monuments, plaques or markers of the uprising, no inclusion of these conflicts in Australia’s many war memorials.

There is still much more work to be done in the field of Aboriginal and Australian history. Uprising, with its emphasis on military tactics, provides a new interpretation of this period of intense conflict. How it can be represented in military history, and in the towns where these events played out, remains an outstanding work for communities and historians.

Heidi Norman is Professor of Australian and Aboriginal History, Faculty of Arts, Design and Architecture, Convenor: Indigenous Land & Justice Research Group, UNSW Sydney

This is an abridged version of an article republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.

Please DO NOT REMOVE. —><img src=”https://counter.theconversation.com/content/253233/count.gif?distributor=republish-lightbox-basic” alt=”The Conversation” width=”1” height=”1” style=”border: none !important; box-shadow: none !important; margin: 0 !important; max-height: 1px !important; max-width: 1px !important; min-height: 1px !important; min-width: 1px !important; opacity: 0 !important; outline: none !important; padding: 0 !important” referrerpolicy=”no-referrer-when-downgrade” /><!— End of code.

If true, the photo’s history is a damning indictment of the systematic exploitation of non-Western journalists by Western media organisations – a pattern that persists today, posit KATE CANTRELL and ALISON BEDFORD

Gin Lane by William Hogarth is a critique of 18th-century London’s growing funeral trade, posits DAN O’BRIEN

BLANE SAVAGE recommends the display of nine previously unseen works by the Glaswegian artist, novelist and playwright

Reading Picasso’s Guernica like a comic strip offers a new way to understand the story it is telling, posits HARRIET EARLE