RITA DI SANTO draws attention to a new film that features Ken Loach and Jeremy Corbyn, and their personal experience of media misrepresentation

STEVE ANDREW enjoys an account of the many communities that flourished independently of and in resistance to the empires of old

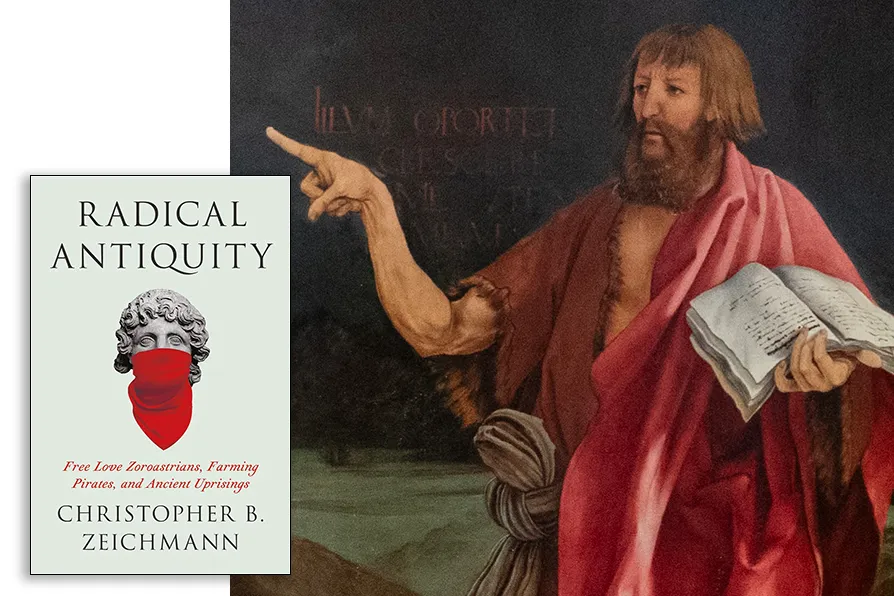

ANTI-STATIST, PACIFIST VEGETARIAN John the Baptist, as depicted by Matthias Grunewald in the Isenheim Altarpiece (1516) is argued to have been a member of the Essene community [Pic: Unterlinden Museum/Gsimonov/CC]

ANTI-STATIST, PACIFIST VEGETARIAN John the Baptist, as depicted by Matthias Grunewald in the Isenheim Altarpiece (1516) is argued to have been a member of the Essene community [Pic: Unterlinden Museum/Gsimonov/CC]

Radical Antiquity: Free Love Zoroastrians, Farming Pirates, and Ancient Uprisings

Christopher B Zeichmann, Pluto Press, £16.99

RADICAL ANTIQUITY is a thought-provoking collection of short essays written from a broadly historical and anthropological perspective, its unifying theme being the exploration of moments in ancient history when peoples and whole societies not only fiercely resisted political repression and economic exploitation, but also tried to replace them with more peaceful, just and cooperative, if not actually communist forms.

Zeichmann’s central argument is that, despite modern-day assumptions, “many people of antiquity found the state an encumbrance that could be readily discarded in favour of something more equitable and empowering.” He goes on to quote Pierre Clastres, the French political anthropologist (1934-77) to the effect that even in our time “many supposedly ‘primitive’ societies decisively reject this form of governance.“

And it’s undoubtedly true that throughout the book Zeichmann succeeds in finding “evidence of radical lives, lived radically.“

Some of the examples discussed are well known, some far less so, but even where stories are familiar Zeichmann often manages to look at them from a different angle and, in the absence of definitive evidence, to ask new questions replete with emancipatory possibilities.

One of my favourite chapters was about the Spartacus uprising and its aftermath. Known to classical historians as the third servile war of 73-71 BC, this revolt massively differed from the previous two in that, with the exception of military expertise provided by Spartacus, it never had any true leader, disdained the use of money, was roughly egalitarian and was largely free of sexual violence. While the uprising itself has now become a major part of Marxist culture and aesthetics, I’d never before read an assessment of the nature of the society subsequently created. Zeichmann’s lengthy discussion around this is both original and fascinating.

Notes on the Therapeutae of Egypt, the Essenes in Judea and the Zoroastrian dissidents, the Mazdakites, all of whom are seen to be anti-statists, pacifist and vegetarian, put the text on a more religious footing. Likewise, the geographically isolated anarcho-primitivists of Phrygia are depicted as living an existence free from the interference of the more rigidly hierarchical and militaristic empires of Persia, Greece and Rome.

The chapter Self-Governance On The Open Sea is nothing short of fantastic. Like many a left-wing account it finds much of value in the world of piracy and it’s incredibly hard not to swept up by the power not only of history but also of myth with all its attendant romanticism.

Less convincing were the chapters on the Cynics which seems to focus more on the beliefs of individuals rather than on attempts to transform wider society. In addition, I felt that the brief entry about the Sami people of Scandinavia lacked both substance and direction.

Zeichmann often emphasises that “Empires exerted minimal influence in rural and peripheral areas” and how “life was remarkably free for anyone more than half a day’s walk from a city.“ In some instances this might be true but it could be an unhelpful generalisation, not least because its conflates the absence of a centralised state presence with liberation. If, say, Greek cities weren’t the areas of participatory democracy some have made them out to be, then neither were others always rural arcadias. The absence of overt state repression on a day-to-day basis often quite happily coexisted with slave-based, brutally patriarchal and oppressive forms of feudalism.

Similarly, the early passage discussing “anarchy“ was both weak and ahistorical, and later notes about this are both laboured and unnecessary. Zeichmann rightly criticises historians for speaking over their subjects and making society fit their own right-wing conservative viewpoints, but seems oblivious to the fact that this is what he is also sometimes in danger of doing, albeit from an overtly progressive viewpoint.

Anarchists will no doubt find much to celebrate here, and the book certainly overturns reactionary notions of human behaviour as intrinsically brutal, competitive and selfish. More orthodox Marxists might well add a note of caution, pointing out that however worthy these attempts were, people make history not always in circumstances of their own choosing and that pre-capitalist moves to create communism were all doomed to failure on the basis that the material conditions were not yet ready for it.

But, whatever your brand of politics, this charming book is an unusually exciting and memorable text and the inclusion of very up-to-date reading lists only adds to the sense that further discoveries are yet to come.

Very much recommended.

STEVEN ANDREW is ultimately disappointed by a memoir that is far from memorable