WILL STONE is frustrated by a performance that chooses to garble the lyrics and drown the songs in reverb

Error message

An error occurred while searching, try again later.MIKE DUGGAN views the maps that renowned sci-fi writer Ursula K LeGuin used to make her fictions, and draws attention to the way such drawings circulate in society

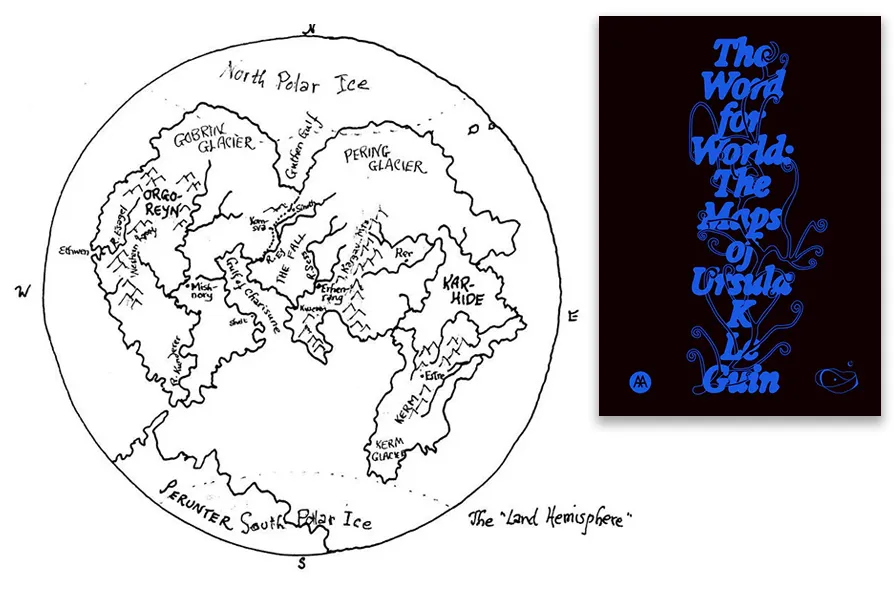

Map of the planet Winter, from LeGuin's novel The Left Hand Of Darkness [Pic: © Ursula K. Le Guin Literary Trust/CC]

Map of the planet Winter, from LeGuin's novel The Left Hand Of Darkness [Pic: © Ursula K. Le Guin Literary Trust/CC]

ONE of the most prolific science-fiction writers of the last century, Ursula K. Le Guin was revered for her inventive, genre-defying novels. Exploring humanity through philosophy, gender, race and society, her stories were rooted in fantasy worlds for which she often created original maps. Now a new exhibition in London is celebrating the cartographic imagination of this groundbreaking US author.

The Word for World: The Maps of Ursula K. Le Guin (Edited by So Mayer and Sarah Shin, Silver Press, 2025) reveals how maps were central to the other-world building she was so famous for. Fans will find much to enjoy here, including the opportunity to walk around enlarged screenprints of well-known maps from books such as Earthsea and Always Coming Home. They will also have the chance to pore over unpublished maps and artworks from the Le Guin Foundation archive.

Thanks to the accompanying book of the same name, readers will be be able to absorb a deeper sense of maps as world-making and storytelling devices, as scholars and commentators discuss their significance in Le Guin’s oeuvre.

Much has been said about the ways Le Guin began her writing process by drawing a map, where she would place characters and narratives in the bounded space of an world etched out in cartographic form. This was as much a way for her to imagine a world as it was a technique to structure a story about it.

There is now an established field of maps studies called literary cartography that explores the way writers of fiction, poetry and folklore use maps in storytelling. It also examines how literary maps, printed alongside the stories they shape, are used by the reader as a way into a world and a device for understanding it.

It is here that maps take on a life of their own as they seep into the imagination of the reader, becoming a well-loved and remembered part of the story.

The exhibition tells us about the context in which maps are understood and how maps circulate in society, creating new meanings along the way.

In the gallery space, Le Guin’s maps are looked at in isolation rather than relating directly to a text. They demand a different kind of attention, for there is a different form of visual connection between a viewer and a gallery object than between a reader and a book. The maps are taken out of their original context and placed in another, but this isn’t to say this new context is any less significant.

My research has shown that the circulation of maps in a society is as important as what’s on the maps themselves. The context of where a map is used, and who it is used by, matters. Those with the power to shape a narrative with a map can have more impact than those that do not.

Consider, for example, the way maps are used in migration debates to show clear delineation of who belongs and who does not. Those with the ability to enforce and debate the border lines shown on the map have far greater power than the migrants that might use the same maps to try to cross them.

Bruno Latour’s immutable mobiles theory resonates here — the idea that what’s on a map remains stable, but the map itself is mobile as it circulates among different people with different interests.

Who maps are seen by, how they are understood, and where they end up are key considerations for map scholars. The Word for World exhibition is a good example of where literary cartographies circulate in society, and where new meanings emerge.

Much of Le Guin’s work is grounded in a belief that humans and other species are completely entangled with their natural environments. When read within the context of the story, Le Guin’s maps illustrate these entanglements by showing how the landscapes of her fictional worlds shape the actions of the characters.

When read outside of the book, in the context of the gallery, the role of the map changes despite it showing the exact same thing. It makes me wonder how Le Guin would understand the new ways that her maps are being read here.

This is even more the case when we think about the function of the maps in her stories — creating other-worlds that tell fictional, but no less real, narratives about racial, gendered and environmental politics. What does it mean to extract a map from the thorny issues of these politics, to be recontextualised as an aesthetic gallery object?

There will forever be a tension between the map exhibition and the ways that maps are encountered in books. By definition they are being “exhibited” and put at the centre. And there’s no doubt Le Guin’s maps look impressive here, masterfully hung, printed on deep blue cotton, bathed in warm lighting.

Draped thoughtfully in rows throughout the space is perhaps a nod to being immersed in the cartographic imagination of Le Guin. They are certainly a spectacle that encourages a closer look. But is that enough?

There is a common fascination with maps, partly to do with their complexity and the invitation to view one’s self in them, which makes them popular objects to exhibit. It’s no surprise then, that the maps do the heavy lifting here, but they are only half the story of the show.

Understanding them more fully means viewing them alongside reading Le Guin’s books, and the show’s accompanying book, which is so much more than an exhibition glossary. It puts the maps into conversation with critical texts on what they meant to Le Guin, but also how they fit into broader discussions about what maps do in the worlds of our imagination.

The Word for World: Maps of Ursula K Le Guin is showing in the Architectural Association Gallery, London until December 6

Mike Duggan is a lecturer in digital culture and technology, King’s College London

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.

![]()