As tens of thousands return to the streets for the first national Palestine march of 2026, this movement refuses to be sidelined or silenced, says PETER LEARY

Error message

An error occurred while searching, try again later.10 years ago this month, Corbyn saved Labour from its right-wing problem, and then the party machine turned on him. But all is not lost yet for the left, says KEITH FLETT

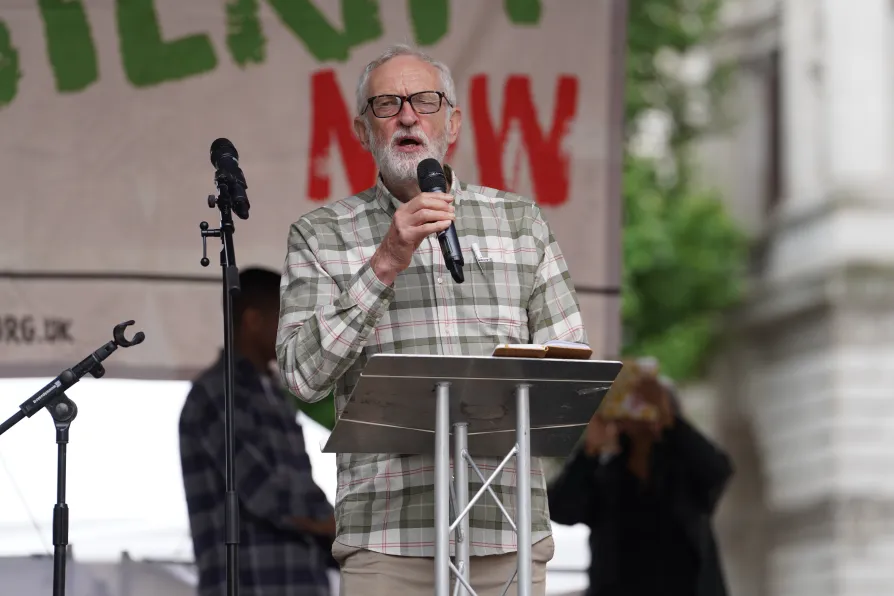

Former Labour Party leader Jeremy Corbyn speaking at the People's Assembly Against Austerity protest in central London, June 7, 2025

Former Labour Party leader Jeremy Corbyn speaking at the People's Assembly Against Austerity protest in central London, June 7, 2025

IN 2025, discussion on the left is about how to shift a Labour government towards pursuing a more left-wing or at least social democratic agenda. For example, a clear break from austerity, a wealth tax, an end to cuts on benefits and a clear anti-racist position. Alternatively another focus is whether it’s possible to create an alternative left-wing political structure to challenge Labour on this basis.

The media is highly unlikely to remember it or feature it but 10 years ago this month, June 2015, a potential answer to these points arose.

Ed Miliband had lost the 2015 general election, with an unexpected win for Tory leader Dave Cameron. Miliband had led Labour mildly from the left but at the election the party had not decisively broken from Tory austerity, or developed a clear anti-racist policy. In fact on the party’s EdStone — a series of modest demands suggesting no clear break from the previous five years of Tory and Liberal Democrat coalition — it pledged the reverse.

On May 8 2015 Miliband resigned as Labour leader, and Harriet Harman became interim leader. Nominations from MPs for a new leader opened on June 8 and closed on June 15.

Thirty-five MPs needed to nominate a candidate for them to make the ballot. Andy Burnham and Yvette Cooper easily cleared the threshold. Two others also did so. Liz Kendall from the Labour right, whose campaign manager was the then unknown Morgan McSweeney, and Jeremy Corbyn.

Corbyn just got over the line with 36 nominations. A number of MPs, including my own, David Lammy in Tottenham, made it clear that while they did not fully agree with the Islington North MP, they felt it was important that there was a voice from the left on the ballot. This idea of Labour as a broad church of left and progressive views has since been abolished by Keir Starmer.

It’s too soon to write a formal history of this period — although there are a number of accounts from people involved in Corbyn’s campaign. I do remember well the moment it was announced that he had got a place on the leadership ballot. In an evening activists’ meeting in north London, someone found the news on Twitter. There was obvious enthusiasm in the room. The possibility of a left campaign had not seemed that likely.

Corbyn had started his political life as a Haringey Labour councillor and then became the Labour MP for Islington North in 1983. As chair of Haringey TUC we worked with him over a sustained period and backed his candidacy for Labour leadership.

Looking back at media releases done at the time the appeal of a clear anti-austerity politics and a break from a situation where the rich made the poor pay for economic crisis is clear.

Subsequently commentary has appeared that this was all a north London bubble not reflected elsewhere in the country. It wasn’t.

The leadership election was held under a new system of One Member, One Vote. This allowed people to sign as Labour supporters for £3 and get a vote for leader.

The result was again unexpected. By the time of the result in September 2015 Labour membership had risen to 552,000 with 112,000 of those being the £3 registered supporters who had mostly joined from June.

The anti-austerity and anti-neoliberal mood built not just an election campaign for Corbyn but the beginnings of a popular movement.

It might be argued that the rest is history, but at 10 years it isn’t yet. The history is still being written and the left still has a chance to shape what the history books of the future will say.