As tens of thousands return to the streets for the first national Palestine march of 2026, this movement refuses to be sidelined or silenced, says PETER LEARY

IN FEBRUARY 1930, the astronomer Clyde Tombaugh spotted what seemed to be a larger than usual object. It was moving in the Kuiper belt, a disc of small remnants left over from the creation of the Solar System that circle around the sun beyond the orbit of the planet Neptune.

Further photographs confirmed the discovery. In May of the same year the name Pluto was announced for the newest and smallest planet, bringing the total number of planets in our Solar System to nine.

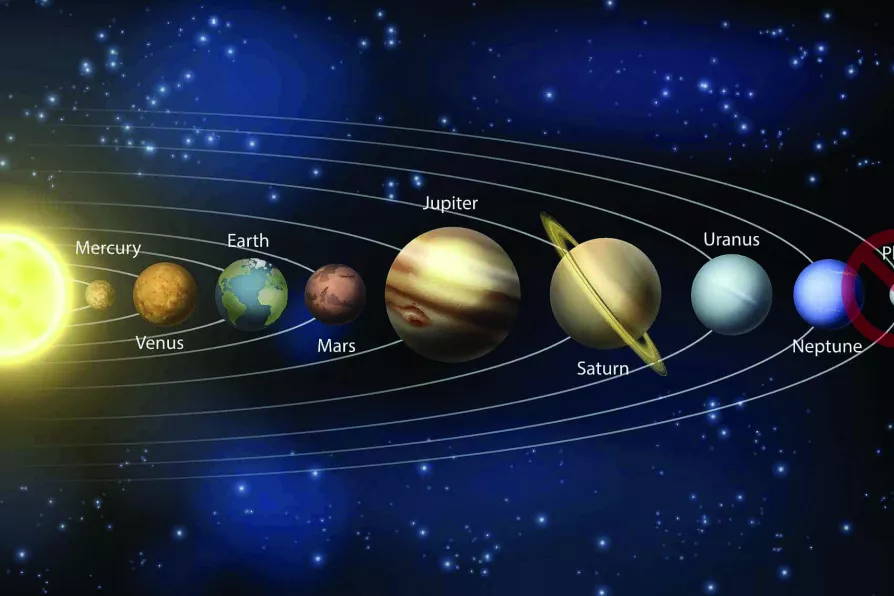

The word “planet” derives from the ancient Greeks’ word for “wanderer.” They distinguished five planets that they could see with the naked eye (Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter and Saturn) because they “wandered” across the background of the other points of light in the night sky — the stars — over the year.

Hiding among the “fixed” stars were Uranus and Neptune, which are often visible to the naked eye but whose slow orbits hid them from being recognised as planets until telescopes were powerful enough for people to notice their small changes in position.

The established process of adding newly discovered, relatively large celestial objects orbiting the Sun to the list of planets ran into trouble in the early 1990s. Scientists began to discover other large objects in the Kuiper belt that had similar characteristics to Pluto.

The first was the catchily named 15760 Albion, found in 1992. Although it was smaller than Pluto, it demonstrated that other objects were waiting to be discovered floating around beyond Neptune in the Kuiper belt.

In 2005 the discovery of Eris, which was initially thought to be larger than Pluto, blew the debate over what constitutes a planet wide open. Surely if Pluto counted as a planet, then Eris must be crowned the tenth planet.

However, if Eris was a planet, then why wasn’t Albion also a planet? And if Albion was a planet, then what about the hundreds of other similarly sized objects that were now regularly being discovered in the Kuiper belt?

The International Astronomical Union held a 10-day meeting in Prague to debate amongst its members and decide on the official definition of a planet.

After several draft proposals they decided that a planet “is a celestial body that a) is in orbit around the Sun, b) has sufficient mass for its self-gravity to overcome rigid body forces so that it assumes a hydrostatic equilibrium (nearly round) shape and c) has cleared the neighbourhood around its orbit.”

This definition meant that neither Pluto, Eris, nor Albion were planets since they had not “cleared their neighbourhood.” This refers to how the gravitational forces exerted by objects with sufficient mass make other smaller objects around them come towards and eventually collide with them, orbit around them as a satellite, or leave the neighbourhood on an altered trajectory.

As of August 2006, Pluto was reclassified as a “dwarf planet.” Dwarf planets meet criteria a) and b) above but have not cleared their neighbourhood. They are also not themselves orbiting another planet or dwarf planet (like a moon).

The reclassification was not happily received in all circles. A satirical resolution, nevertheless backed by 52 other members of the California State Assembly with varying levels of credulity, denounced the decision and claimed that the change would “cause psychological harm to Californians who question their place in the universe and worry about the instability of universal constants.”

Although intended by its originators as a joke, this quote identifies the problem many of us face when “facts” change in science, not through new evidence, but through new analysis.

JOHN GREEN’s palate is tickled by useful information leavened by amusing and unusual anecdotes, incidental gossip and scare stories

Neutrinos are so abundant that 400 trillion pass through your body every second. ROX MIDDLETON, LIAM SHAW and MIRIAM GAUNTLETT explain how scientists are seeking to know more about them

Science has always been mixed up with money and power, but as a decorative facade for megayachts, it risks leaving reality behind altogether, write ROX MIDDLETON, LIAM SHAW and MIRIAM GAUNTLETT