GEOFF BOTTOMS applauds a version set amid the violent conflicts of the 19th century west African Oyo empire before the intervention of British colonialism

Error message

An error occurred while searching, try again later.An ambitious and enjoyable inquiry into what we mean by new is marred by a lack of materialist analysis and anti-communist bias, suggest MARTIN HALL

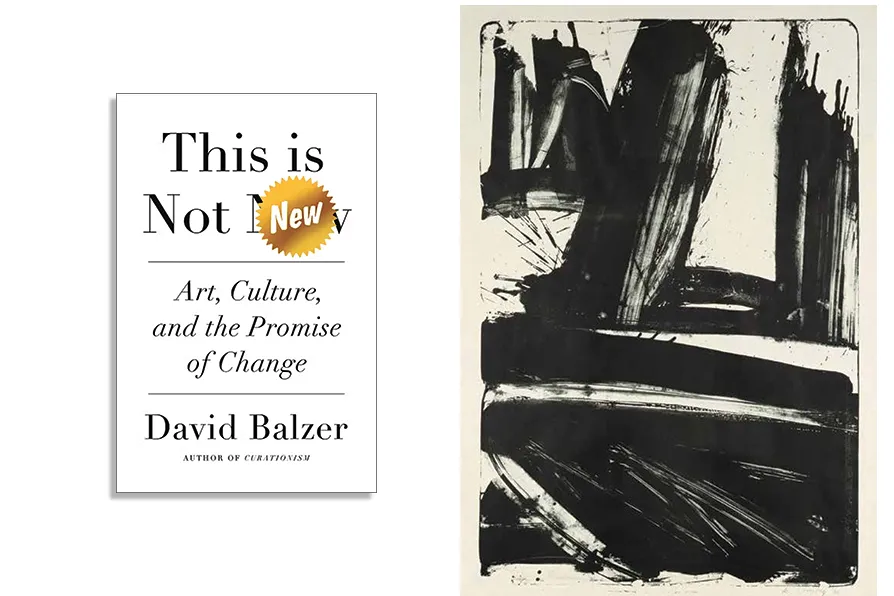

ART DEPOLITICISED: Litho #1 (Waves #1) by Willem de Kooning, 1960, who was part of the abstract expressionism movement / Pic: Public domain

ART DEPOLITICISED: Litho #1 (Waves #1) by Willem de Kooning, 1960, who was part of the abstract expressionism movement / Pic: Public domain

This is Not New: Art, Culture, and the Promise of Change

David Balzer

Pluto Press, £16.99

DAVID BALZER presents an interesting and enjoyable intervention into something that many take for granted, but which is a relatively recent development: what do we mean by the “new”? What does that mean under capitalism, and why does it endure in the so-called postmodern age?

This is explored in a somewhat quixotic fashion, rather than systematically, via a long essay with a postscript on Kate Bush’s experiments with new ways of producing music. This is typical of Pluto Press and does fit a commentary on culture, because it perhaps mimics artistic interventions themselves.

Initially, there is a discussion of a selection of radicals: Goya, the Futurists, and Cindy Sherman. With the former, Balzar looks at his 1823 work, Satan Devouring His Son, to set out his argument regarding the (in)efficacy of the “new” as concept: it influenced Sherman’s filmic and televisual restagings in the 1980s, and was itself influenced by a Rubens sketch, as well as being a story from antiquity.

Despite this temporal line, the painting is commonly seen as a rupture, and one that “disrupted the European tradition so thoroughly as to birth another: the modern, the avant-garde, even the punk”.

Balzar posits that the way in which it became new is typical of how the West assigns radicalism and innovation to its artists. A part of this is a refusal to please an audience, a production trope that we have grown used to in popular culture since at least the time of punk, but one which is often assigned to modernist and proto-modernist movements in fine art, literature and also film.

To turn to the first chapter proper, Culture Industry, Culture Wars, it sets out in shorthand the arguments of Theodor Adorno and Max Horkheimer of the Frankfurt School, along with those of their less pessimistic colleague, Walter Benjamin.

Every Humanities post-grad on a theory course will have encountered Adorno & Horkeimer’s work, and will be familiar with it: the privileging of high over mass art, and a concomitant attempt to understand how culture works under capitalism, namely: popular culture’s relationship to the Enlightenment idea of progress, though one diluted by mass production and modes of exhibition unconducive to intellectual enquiry. Of course, this is indicated in the title of their most well-known work, Dialectic of Enlightenment, though the extent to which it employs a Marxist dialectical method is a matter of contention.

That aside, Balzar’s discussion allows him to set out a dialectic: between that of the pessimists (Adorno and Horkheimer) and the optimists, Antonio Gramsci, Benjamin and Stuart Hall. This is well-worn territory, though the author does provide insights and a framework for thinking about how concepts such as the dominant culture/cultural hegemony survive (or not) in the internet age. However, such arguments would be aided by a Marxist understanding of class, as well as a broader range of cultural reference points.

The second chapter considers the utopian as a category, the new as a conceptual model, and the role of science in the relevant debates, and in particular, the very important work in the 1960s of Thomas Kuhn. While no proto-postmodernist, his taking to task of teleological, linear concepts of progression, rupture and the new does pave the way for an understanding of culture as pattern-based, circular and relational. Paradigms and associated debates regarding their supposed shattering or recalibration are central to discussion of the new to this day.

The last chapter considers the relationship between European and US art (a key interest of Adorno, of course). The CIA was key to the art world moving from Paris to New York, aided by the depoliticisation of the abstract expressionists (as they would become) from the 1930s onwards.

Unfortunately, the politics of this – an opposition to Stalinism during the show trials – is presented as inevitable, with no comment made regarding the role of the US state here. Instead, we are presented with depoliticisation as simply predicated upon a quite “natural” intellectual change of path. This is a shame, as situating consciousness materially in order to understand the political climate in which this move took place would provide a fuller understanding of what happened.

In general, Balzar’s thinking does fall victim to anti-communism, and in so doing he accepts and propagates shibboleths regarding totalitarianism and culture, to give one example.

While the book does mostly achieve what it sets out to do, its theoretical frame of reference keeps it anchored in the very debates it attempts to critique; ironically, he talks about the difficulty of discussing culture while within it, and the same can be said for this book and hegemony tout court.