JAMES NALTON on Munyua’s stinging success at the World Darts Championship

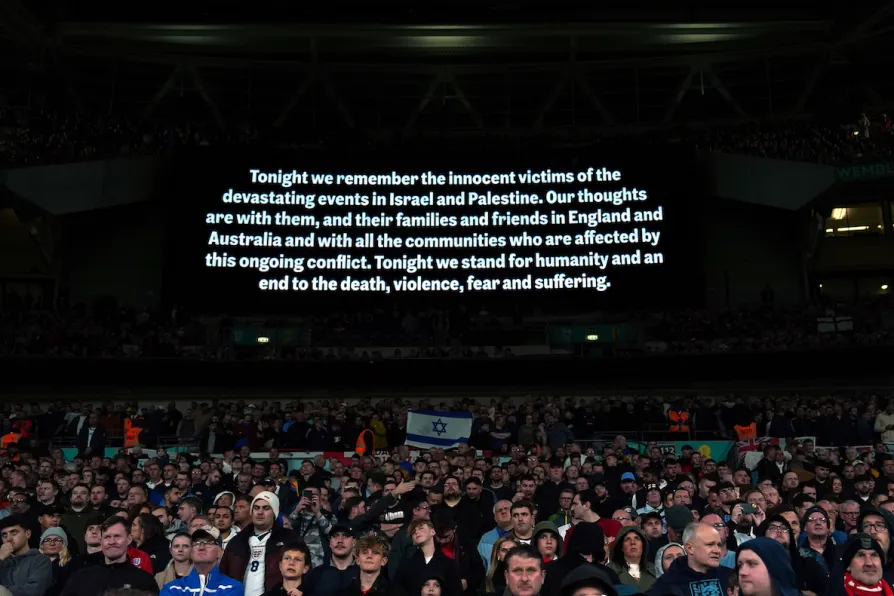

A message of support for the victims in Israel and Palestine ahead of the international friendly match at Wembley Stadium, London.

A message of support for the victims in Israel and Palestine ahead of the international friendly match at Wembley Stadium, London.

IN SELLING itself to the highest bidders, which now happen to be sovereign states, rich monarchies and the tools of exploitative global capitalism, top-level football has entered the world of politics by default.

From the economic politics of capitalism to the geopolitics of state ownership and the increased intertwining of the two, football is part of these systems because it is now owned, directed and influenced by them.

Combine this with its own inherent political geography and power dynamics, created by various divisions, tournaments and confederations within a global structure, plus its links to society, communities, businesses and its own economy and workforce, and football is now almost a branch of political science itself.

In recent years, the sport has increasingly sold its way into the realms of other branches of politics, such as economics and international relations.

Along with this comes the inevitable task of making political decisions, gestures and statements.

It is here that top-level football can find itself out of its depth and out of tune, under pressure from the world powers it sold itself to and their Establishment media.

This has become increasingly apparent in the years since football became a tool for imperialists — for states and absolute monarchies and for groups whose names often include “private equity” and “investment”—a guise for the useless, unproductive and exploitative practice of making money from money.

When it became more complicated than simply taking the side of your team against the other team, football struggled to know what to do.

It began to hold pre-match rituals related to the global events it was now involved in, having to take sides in political debates and current affairs or respond to recent events quickly and in a manner deemed appropriate.

This was easier at first despite the occasional backlash, but it became increasingly difficult to find the “appropriate” action.

As the sport was sold around the world to different groups with different backgrounds and ideologies, there would inevitably be clashes.

This has culminated, for now — as it feels like so much of the world’s politics has — around the continuation of the situation in Israel and Palestine.

With the entire world now focused on this one region and on this one issue, football was expected to act, but in what manner?

As the English FA and Premier League found out, there is no simple pre-kick-off gesture that safely and uncontroversially deals with such an issue.

In the end, the furore focused on the possibility of lighting up the Wembley arch in the colours of the Israel flag ahead of the game between England and Australia on October 13, six days after the Hamas terrorist attacks in Israel.

The relatively trivial lighting of an arch on a stadium became a big issue in the media.

Maybe it was because talking about this felt safer and more comfortable than writing about what is actually going on and the whys and wherefores.

The FA, to its credit, did well to ignore those insisting that the arch be lit up in the colours of the Israel flag while Palestinian civilians were being killed by the Israeli government and its army.

It was an abhorrent, sickening terrorist attack by Hamas in Israel, in which hostages were taken. It wasn’t an unprovoked one. It was one that Israel has responded to with the same barbarity and then some.

This kind of attack on the Gaza Strip by Israel is not unfamiliar to Palestinians trapped there.

They have been subjected to such violence, danger and death at the hands of Israel for as long as people can remember.

This is why the arch could not be lit up in the colours of the Israeli flag, despite the terrorist attacks in Israel days earlier.

In the end, the FA did the right thing in those circumstances at that time, but FA chairman Mark Bullingham still described it as “one of the hardest decisions we’ve had to make.”

Meanwhile, journalists and media outlets, including football writers, demanding that the arch be lit up and then decrying the FA for not doing so when it wasn’t, is one of the many Western responses the crisis that beggar belief.

Working journalists were among those killed by Israel in the days leading up to that game at Wembley.

In the isolation of the profession, showing support for an oppressor who has killed colleagues among the thousands of trapped civilians is hardly a show of solidarity.

Amid the grim reality of life on the ground in the region, there will be little care for the lighting of an arch on a football stadium, though other shows of support will be seen and welcomed by many whose family and friends are in the worst situations.

Those in Israel who were attacked on October 7 while going about their daily lives, and their friends and families around the world, not just in Israel, need more than empty symbolism anyway.

They need real support in communities where the actions of the Israeli government and its army, supported and armed by the West, have led to waves of anti-semitism affecting Jewish communities.

Just as there was an increase in Russophobia on the back of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, there have been similar attacks on Jewish civilians around the world on the back of Israel’s devastating bombardment of Gaza.

It is in those communities that support is needed, alongside the continued fight against anti-semitism.

A flag can be one way of showing support, but given that Britain provides arms to the Israeli government and has supported the atrocities it inflicts on Palestine for so long, displaying Israel’s colours on the national stadium could have been viewed as a show of aggression against Palestinians suffering ongoing oppression and attacks.

Those on the ground in Palestine who have faced barrage after barrage from across the border for generations need support from the international community.

But for a few weeks, we had the almost unbelievable scenario where Western leaders and their media, rather than just condemning the terrorist attack by Hamas, were actively backing Israel’s brutal response.

The ban on Maccabi Tel Aviv fans was based on evidence of a pattern of violence and hatred targeting Arabs and Muslims, two communities that have a large population in Birmingham — overturning the ban was tacit acceptance of the genocidal ideology the fans espouse, argues CLAUDIA WEBBE

With foreign media banned from Gaza, Palestinians themselves have reversed most of zionism’s century-long propaganda gains in just two years — this is why Israel has killed 270 journalists since October 2023, explains RAMZY BAROUD

Israel’s messianic settler regime has moved beyond military containment to mass ethnic cleansing, making any two-state solution based on differential rights impossible — we must support the Palestinian demand for decolonisation, writes HUGH LANNING

The PFA is urging Fifa action against illegal Israeli settlement clubs and incitement to genocide, writes JAMES NALTON