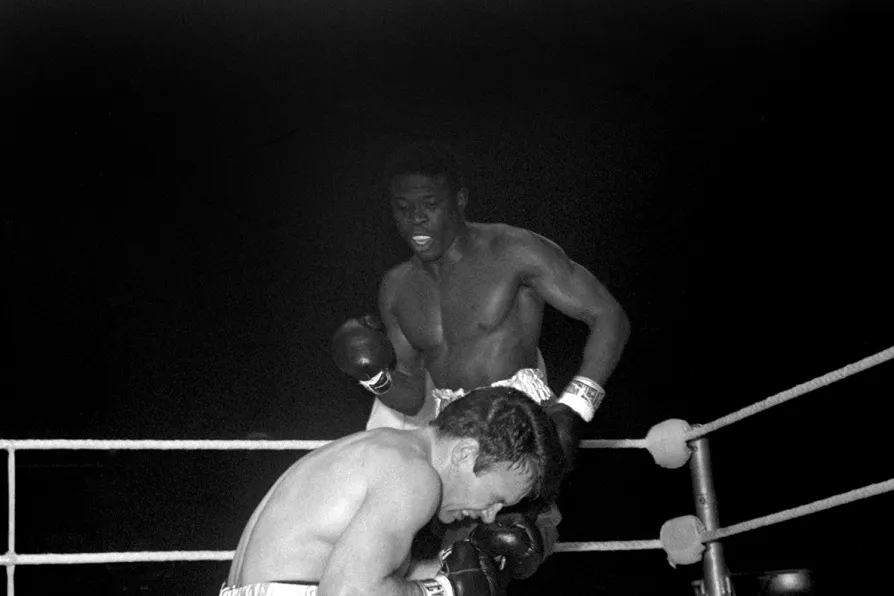

British lightweight boxing champion Dave Charnley receives a blow from world welter-weight champion Emile Griffith in December 1964

British lightweight boxing champion Dave Charnley receives a blow from world welter-weight champion Emile Griffith in December 1964

HARD enough being a young black man in the United States during the long and oppressive Jim Crow decades of the 1950s and 60s, forced to suffer a daily assault on your dignity, humanity, and often even personal safety. Imagine, then, what it was like to be not just black, but also gay at a time when homosexuality was deemed a criminal offence in the land of the free. Then consider the particular challenges involved in being black, gay, and a boxing world champion to boot.

“There is no education like adversity,” so goes the aphorism, one that could have been written with the remarkable life of Emile Griffith in mind. His 112 professional fights, stretching 19 years from his ring debut in 1958 to his last fight in 1977, after which he finally accepted that he had “nothing more to prove,” could never come close to competing with the struggle against adversity he fought on the other side of the ropes.

For Griffith, a man whose ambition in life as a young man was never to win fame and fortune in the hurt business but to make ladies’ hats, the ring was not an arena where men risked all but rather a sanctuary and an escape from the constant pressure of concealing who he really was.

When Patterson and Liston met in the ring in 1962, it was more than a title bout — it was a collision of two black archetypes shaped by white America’s fears and fantasies, writes JOHN WIGHT

JOHN WIGHT previews the much-anticipated bout between Benn and Eubank Jnr where — unlike the fights between their fathers — spectacle has reigned over substance