As tens of thousands return to the streets for the first national Palestine march of 2026, this movement refuses to be sidelined or silenced, says PETER LEARY

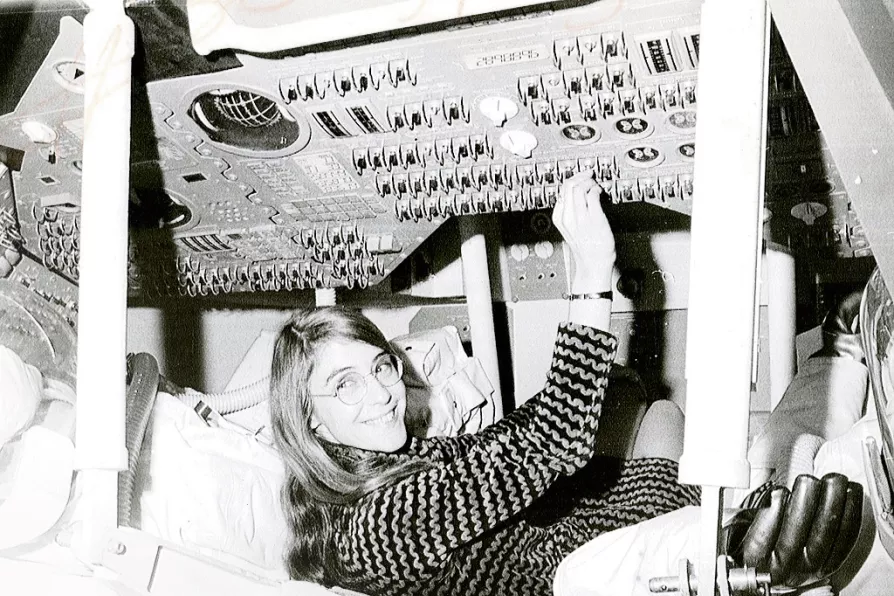

Margaret Hamilton, who led the flight software team of Apollo 11

Margaret Hamilton, who led the flight software team of Apollo 11

THIS month marked the 50th anniversary of Apollo 11 — the first successful moon landing. A great deal of coverage focused on the three male astronauts who set foot on the moon, but the work to get them there required hundreds of thousands of people.

Todd Douglas Miller’s new documentary about the events, Apollo 11, uses newly discovered 70mm film from the Nasa archives to tell this story of collective achievement.

Rather than simply showing us Armstrong, Aldrin and Collins throughout the eight-day mission, Miller includes detailed footage of the Nasa employees working on the ground to make sure the mission succeeded.

What’s behind the stubborn gender gap in Stem disciplines ask ROX MIDDLETON, LIAM SHAW and MIRIAM GAUNTLETT in their column Science and Society

200 years since the first dinosaur was described and 25 after its record-breaking predecessor, the BBC has brought back Walking with Dinosaurs. BEN CHACKO assesses what works and what doesn’t