As tens of thousands return to the streets for the first national Palestine march of 2026, this movement refuses to be sidelined or silenced, says PETER LEARY

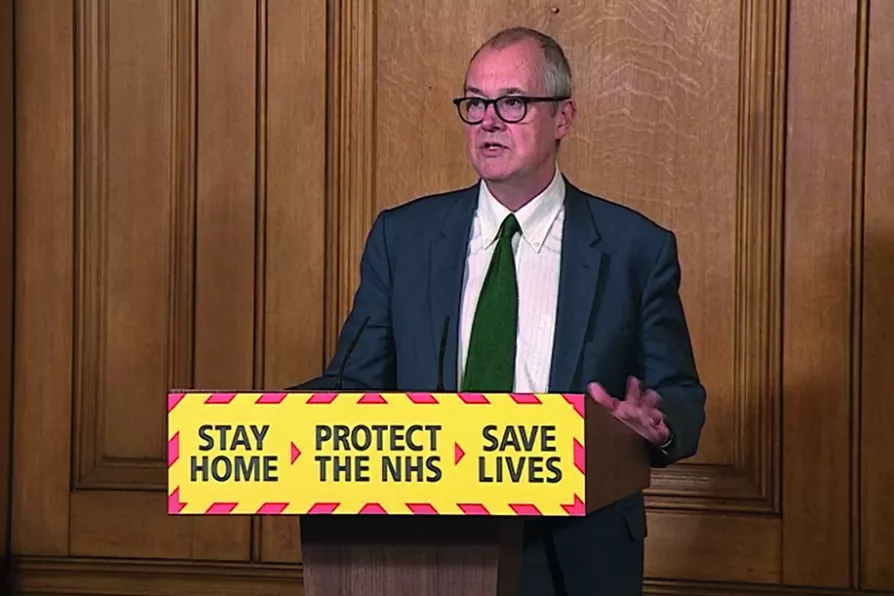

The government's chief scientific adviser Sir Patrick Vallance

The government's chief scientific adviser Sir Patrick Vallance

WHEN politicians seek to use science as a facade of authority, scientists need to watch out for the backlash.

As the government has plunged Britain into the crisis of being among the worst-hit countries in the world during the Covid-19 pandemic, its members have repeated the mantra again and again that they are being “led by science.”

After the much feted turn away from experts, this change in the language of authority has been remarked upon as a change in public mood caused by the unprecedented crisis.

A maverick’s self-inflicted snake bites could unlock breakthrough treatments – but they also reveal deeper tensions between noble scientific curiosity and cold corporate callousness, write ROX MIDDLETON, LIAM SHAW and MIRIAM GAUNTLETT

Science has always been mixed up with money and power, but as a decorative facade for megayachts, it risks leaving reality behind altogether, write ROX MIDDLETON, LIAM SHAW and MIRIAM GAUNTLETT