The PM says Mandelson 'betrayed our values' – but ministers and advisers flock to line their pockets with corporate cash, says SOLOMON HUGHES

Error message

An error occurred while searching, try again later.From London’s holly-sellers to Engels’s flaming Christmas centrepiece, the plum pudding was more than festive fare in Victorian Britain, says KEITH FLETT

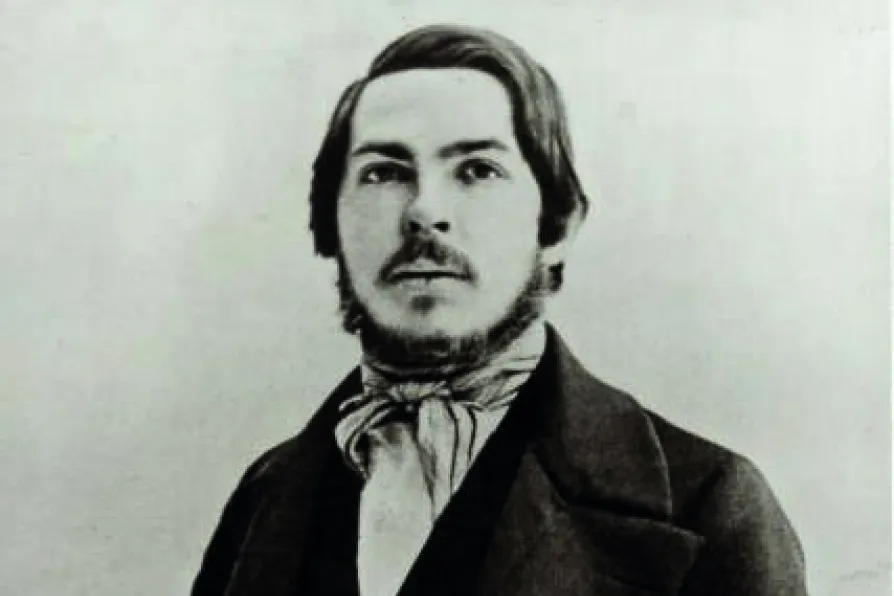

CHRISTMAS TRADITION: Engels sent plum puddings to comrades and relatives in Germany

CHRISTMAS TRADITION: Engels sent plum puddings to comrades and relatives in Germany

THE plum pudding was a staple of the Victorian Christmas, even for the poor. Henry Mayhew described how much seasonal employment the pudding and decorating them with holly provided.

It’s a reminder of how much the seasonal trade in December was relied on by those who knew that the months of January and February would be tough.

Victorian capitalism and capitalism in 2025 both rely on a casualised labour market. We still eat lots of plum pudding too — it’s another name for the Christmas pudding, and signified simply that dried fruit, the plum, actually a raisin in the English pudding, was involved.

Henry Mayhew wrote in London Labour and the London Poor about the Christmas market for plum puddings and holly:

“Well, then, consider,” said another informant, “the plum-puddings! Why, at least there’s a hundred thousand of ’em eaten, in London, through Christmas and the month following. That’s nearly one pudding to every twenty of the population, is it, sir? Well, perhaps, that’s too much. But, then, there’s the great numbers eaten at public dinners and suppers; and there’s more plum-pudding clubs at the small grocers and public-houses than there used to be, so, say full a hundred thousand, flinging in any mince-pies that may be decorated with evergreens. Well, sir, every plum-pudding will have a sprig of holly in him. If it’s bought just for the occasion, it may cost 1d., to be really prime and nicely berried. If it’s part of a lot, why it won’t cost a halfpenny, so reckon it all at a halfpenny. What does that come to? Above £200. Think of that, then, just for sprigging puddings!”

One well-known enthusiast for plum pudding was Engels. Indeed, as his letters make clear, he would have eaten it year round were this not frowned upon by his household.

Engels made a tradition after his retirement as a Manchester businessman of sending plum puddings to comrades and relatives in Germany.

In 2025 Engels might well have been a contestant on Celebrity Masterchef as writing to Laura Lafargue on December 20 1892 he gave precise cooking instructions:

“The pudding is not quite boiled out, our copper would not heat last Saturday and so, instead of twelve hours’ boiling, the unfortunate pudding only got about nine or ten, But if you give it two to three hours’ boiling before serving, it will be all right.”

Engels was on occasion concerned about the consequences of eating too much plum pudding. He wrote to Natalie Liebknecht on December 24 1889 about plans for a Christmas Day party:

“Nimmi is busy cooking and baking — the plum puddings were made a week ago. It’s an awful chore, with no purpose other than to bring on attacks of indigestion! But such is required by custom, and one has to conform. Nevertheless we’ll make merry, even if we’re sorry for it on Boxing Day.”

However as an account by Edward Bernstein in his 1915 memoir underlined, Christmas dinner at Engels’s home 122 Regent’s Park Road did have plum pudding as its centre piece:

“The dish of honour, the plum-pudding, which is served up, the room having been darkened, with burning rum. Each guest must receive his helping of pudding, liberally christened with good spirits, before the flame dies out. This lays a foundation which may well prove hazardous to those who do not measure their consumption of the accompanying witness.”

As ever, though, the plum pudding was washed down with wine and pilsner beer, a tweak on Charles Dickens’s Christmas Carol where the real focus was the turkey.

Keith Flett is a socialist historian.