A survey circulated by a far-right-linked student group has sparked outrage, with educators, historians and veterans warning that profiling teachers for their political views echoes fascist-era practices. FEDERICA ADRIANI reports

Hundreds in Berlin gathered on January 15 to honour the US-born socialist who made East Germany his home. Florentine Morales Sandoval reports

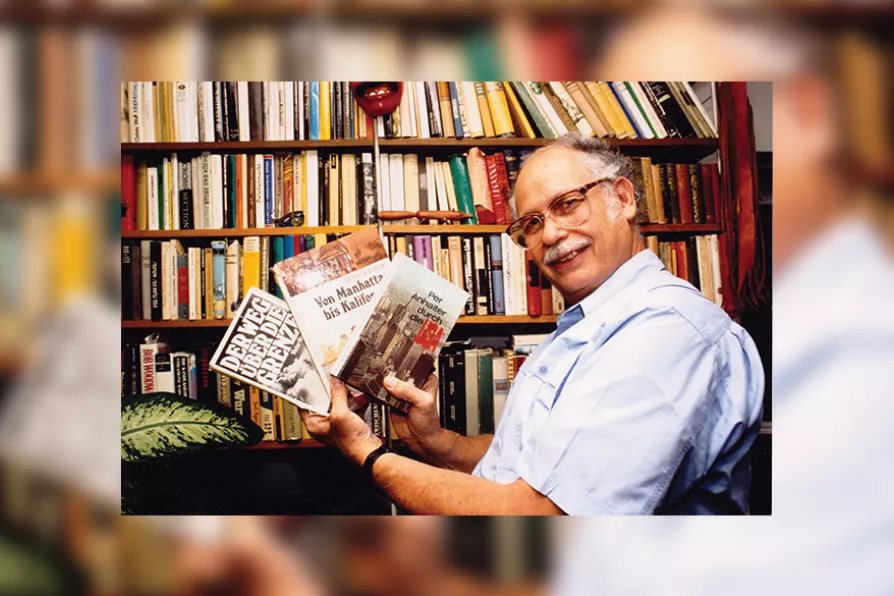

Victor Grossman with some of the works he published in the GDR [Pic: Uli Kohls]

[Uli Kohls]

Victor Grossman with some of the works he published in the GDR [Pic: Uli Kohls]

[Uli Kohls]

ON A COLD January morning in Berlin, around 200 mourners gathered to bid farewell to Victor Grossman, the US-born socialist journalist and author who defected from the US army in 1952 and spent the rest of his life in Germany.

Grossman, born Stephen Wechsler in New York City on March 11, 1928, passed away in Berlin on December 17 2025, at the age of 97.

The memorial service, held on January 15 2026, was a fitting tribute to a man whose life was defined by unwavering commitment to socialist ideals and international solidarity.

The ceremony was steeped in the traditions Grossman cherished. The songs of Pete Seeger and Woody Guthrie filled the hall, alongside music by Ernst Busch and poems from Heinrich Heine.

The banner of the International Brigades — the volunteers who fought against fascism in the Spanish civil war — was displayed prominently, a symbol of the anti-fascist heritage Grossman embodied throughout his life.

Grossman’s extraordinary journey began in 1930s New York, where as a young boy he collected money for the Spanish Republic during the civil war. He joined the Young Communist League at 14 and the Communist Party USA at 17, while still a student.

After earning a degree in economics from Harvard University, he worked as a factory worker in Buffalo, New York, at the party’s request, organising among industrial workers. Drafted into the US army in 1950, he was stationed in Bavaria when he learned he was about to be investigated for his communist affiliations during the McCarthy era.

Rather than face persecution, Stephen Wechsler made the dramatic decision to swim across the Danube River into the Soviet zone of Austria, eventually making his way to East Germany, where he would live for the rest of his life.

In the German Democratic Republic (GDR), he built a new life under his chosen name. He studied journalism at Karl Marx University in Leipzig, becoming, as he proudly noted, “the only person in the world to hold degrees from both Harvard and Karl Marx University.”

He married his beloved Renate and became a freelance journalist, author, translator and tireless advocate for socialist causes. From 1965 to 1968, he directed the Paul Robeson Archive at the Academy of Arts, preserving the legacy of the great African-American artist, singer and activist.

The memorial address was delivered by Sevim Dagdelen, former parliamentarian and current foreign policy spokesperson for the Bundnis Sahra Wagenknecht party (BSW). Dagdelen painted a vivid portrait of a man whose fighting spirit never dimmed with age.

“Just last year,” she recounted, “his children had to talk him out of joining the Gaza flotilla.” The image was quintessentially Grossman: at 96, still ready to put his body on the line for the cause of Palestinian liberation.

Dagdelen traced the arc of Grossman’s political awakening back to his childhood, when he collected money on New York streets to support the struggle against Franco’s fascists. His decision to choose the socialist German state over the US, Dagdelen emphasised, was never one he regretted. It was a choice against US imperialism, and subsequent events, including the rise of Donald Trump, only confirmed his analysis.

“For Victor,” Dagdelen explained, “Trump was not an exception but a confirmation of the system.”

Dagdelen described Grossman as an intellectual whose worldview was shaped less by his academic training than by his years working alongside labourers in Buffalo. He saw the GDR as a society of contradictions — one where genuine social achievements for workers, women and the vulnerable stood alongside undeniable shortcomings. The collapse of East Germany was, for Grossman, a personal defeat. Yet he believed future generations could learn from both the failures and the accomplishments of the socialist experiment.

His solidarity, Dagdelen noted, extended to oppressed peoples everywhere — South Africa, Angola, Palestine. “For Victor, it was never important where someone came from,” she said. “What mattered was what a person thought, how they acted, and where they stood in relation to the workers.” Invoking Walter Benjamin’s famous thesis that even the dead are not safe from the enemy if that enemy wins, Dagdelen called on mourners to continue the struggle against any attempt to distort Grossman’s legacy.

“The fight for liberation,” she declared, “is not only a fight for the living but also for the dead.”

Sabine Schubert, a comrade of Victor and longtime activist in the Free Mumia Abu-Jamal campaign, offered a second tribute that focused on Grossman’s irreplaceable role in East German cultural and political life.

“Anyone who was politically or culturally active in the GDR could not avoid Victor Grossman,” she observed. Schubert emphasised Grossman’s role as a cultural mediator, a bridge between US traditions of protest and folk music and the socialist world. He introduced East German audiences to the history of the US civil rights movement and the rich heritage of US protest songs.

Victor Grossman now rests in the company of other great men and women who devoted their art and life to socialism. The Dorotheenstadtischer Friedhof, where Victor is laid to rest, is the final home to many of the cultural luminaries of the German socialist tradition: Bertolt Brecht and Helene Weigel, Anna Seghers, Heinrich Mann, Hanns Eisler, and Walter Heynowski, among others. Like them, Grossman shared the conviction that culture and politics are inseparable, that songs and stories can change the world.

As Paul Robeson’s Going Home filled the hall at the close of the ceremony, the mourners carried with them the words of both speakers: the struggle continues. “We will carry on, Victor — that’s a promise,” Schubert vowed. She closed her speech with the rallying cry of the Spanish Republic, the cause that first awakened a young boy in New York to the meaning of international solidarity: “No pasaran!” — They shall not pass.

This article is republished from peoplesdispatch.org.

The decision highlights the tension between freedom of expression and the state’s role in shaping historical memory at former concentration camps, reports LEON WYSTRYCHOWSKI

In part two of May’s Berlin Bulletin, VICTOR GROSSMAN, having assessed the policies of the new government, looks at how the opposition is faring