As tens of thousands return to the streets for the first national Palestine march of 2026, this movement refuses to be sidelined or silenced, says PETER LEARY

On the anniversary of the implementation of the 1833 Slavery Abolition Act, ROGER McKENZIE warns that the legacy of black enslavement still looms in the Caribbean and beyond

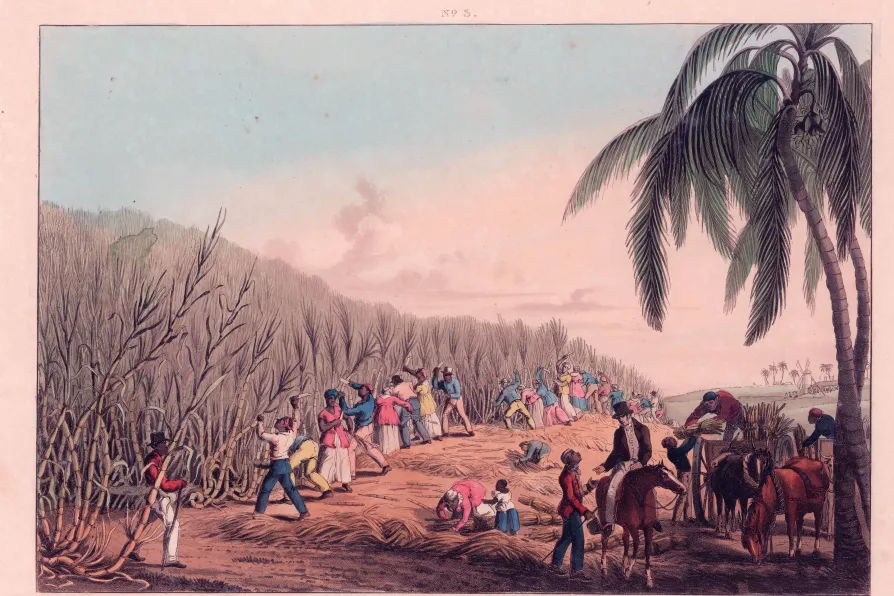

STRUGGLE FOR LIBERTY: Enslaved black people cut the sugar cane and load the bundles or junks into a horse-drawn cart in Antigua, a former British colony

STRUGGLE FOR LIBERTY: Enslaved black people cut the sugar cane and load the bundles or junks into a horse-drawn cart in Antigua, a former British colony

EMANICIPATION Day unfortunately barely raises a flicker here in Babylon. But it represents one of the most symbolic days in British history — the anniversary of the coming into law of the 1833 Slavery Abolition Act.

It celebrates freedom and all those who fought so hard to remove the shackles of enslavement.

My mom was born in the late 1920s and lived into her nineties and her father lived into his nineties, having died in the late 1970s.

As far as I can work out from the records I have been able to gather, my grandfather was the first free-born in my family for centuries.

The point is that this was not so very long ago and yet we constantly hear the plea from many white folks to “stop living in the past,” as if this was some matter of ancient history.

I often wonder whether Emancipation Day would get more attention if it was placed in the neat safe box of Black History Month when everyone could just eat ackee and salt fish or curry goat and rice and peas together and then, come the day after Halloween, forget all about such inconveniences — except the food.

But 3,000 miles or so across the Caribbean — because enslavement was far enough away from the consciousness of most British people to not cause a heart murmur — Emancipation Day is rightly a huge deal.

It still resonates deeply in the collective memory of the people because, as I have pointed out, it really was not that long ago.

The oral traditions of the Caribbean mean that the stories of resistance to enslavement are still told — from day one of the racism that was manufactured as a justification for the brutal, inhumane treatment of Africans under enslavement there was resistance.

More so — there was resistance to enslavement itself from the moment Europeans decided to enslave and transport Africans across the sacred burial grounds otherwise known as the Atlantic Ocean.

Having wiped out the indigenous communities in the Caribbean by overwork and disease, such as the Tainos in Jamaica, the Europeans needed a cheap or, preferably, free form of labour to replace them.

Africans fitted the bill for the Europeans and were hunted down and enslaved with the assistance of “misleaders” on the African continent.

It is estimated that the British forcibly transported more than three million enslaved Africans to the Caribbean between the 17th and 19th centuries, to work on plantations producing crops such as sugar, tobacco and coffee. The figure is likely to be far higher as records are incomplete.

Families and people from the same tribes were routinely separated. This meant that there were significant language barriers faced by the enslaved. Deliberately so. For the slavers this meant it would make it harder to resist the inhumane treatment being meted out in the name of profit accumulation.

But it is also the case that the Caribbean continues to live with the legacy of enslavement to this day. Poverty levels across the Caribbean average around 26-30 per cent.

Across the region basic services such as healthcare, education and clean water are often at a premium. In many places accessing adequate food and nutrition is still a major challenge.

Far too often the young people of the Caribbean are forced to drop out of education because they need to prioritise finding work so that they can put food on the table and keep a roof over their heads.

That’s why Emancipation Day is still a big deal across the Caribbean.

In Jamaica it’s part of a broader cultural celebration called Emancipendence, combining both Emancipation Day and Independence Day (August 6) — deeply rooted in African traditions.

Last year in Trinidad & Tobago Prime Minister Dr Keith Rowley announced a renaming of Emancipation Day to African Emancipation Day.

Rowley said he had taken the step because of what he saw as a concerted attempt to “add appendages” to the reasoning behind emancipation. In the face of attempts to rewrite history, he wanted there to be no doubt that emancipation in Trinidad and Tobago is a result of the emancipation of slaves.

In Barbados there is an annual Emancipation Day walk in the capital Bridgetown from Independence Square to the Emancipation (or Bussa’s) Statue. Bussa was an African-born enslaved man who led a major slave rebellion in Barbados in 1816.

There are plenty of other celebrations and commemorations throughout the British-colonised Caribbean.

In recent years, Emancipation Day has increasingly become a rallying point in the movement for genuine independence from Britain as well as for reparations.

For large parts of the British-speaking Caribbean, the head of state is still Britain’s monarch. The highest court is also still the Privy Council — a formal body of advisers to the British monarch made up mainly from senior politicians who are current or former members of Parliament or the House of Lords.

But it is the issue of reparations that has become a hot issue — or rather the total refusal of successive British governments to contemplate any monetary compensation caused by the enslavement of Africans.

There was, of course, no problem compensating the slavers for their “loss of property” when enslavement ended.

May I take this opportunity to thank all of you that paid taxes up to 2015 for contributing towards my freedom — because that’s when the compensation, which amounted to £20 million at the time (equivalent to £2 billion today) finished being paid off.

This of course also means I have been paying for my own freedom for the vast majority of my working life!

The exact amount of money that the British made from enslavement and the colonisation of the Caribbean is difficult to estimate. But a mere difficulty of maths shouldn’t get in the way of a commitment to providing compensation for the enslaved rather than just the enslavers.

What we do know is that the enslavement of Africans and the colonisation of the Caribbean was highly profitable for the British empire, and played a central role in maintaining Britain’s role as a global superpower.

The profits from enslavement and colonialism allowed the British empire to invest in other industries, such as manufacturing and banking, which further fuelled Britain’s economy.

Yes, whichever way the deniers try to cut it, British wealth was built on the exploitation and oppression of enslaved Africans.

The working class of Britain have already paid — albeit the wrong people (the slavers). But the people and institutions that have really profited from enslavement barely pay any taxes at all. It is time for them to cough up!

Roger McKenzie and Luke Daniels, president of Caribbean Labour Solidarity, will be speaking at an online Communist Party Emancipation Day event today at 7pm in a discussion about the legacy of slavery, imperialism and the struggle for liberation. Register at tinyurl.com/EmancipationD2025.

ROGER McKENZIE argues that Western powers can see the beginning of the end in the rise of the global South — and racist reactions are kicking in

ROGER McKENZIE expounds on the motivation that drove him to write a book that anticipates a dawn of a new, fully liberated Africa – the land of his ancestors

SUE TURNER is appalled by the story of the only original colonising family to still own a plantation in the West Indies