As tens of thousands return to the streets for the first national Palestine march of 2026, this movement refuses to be sidelined or silenced, says PETER LEARY

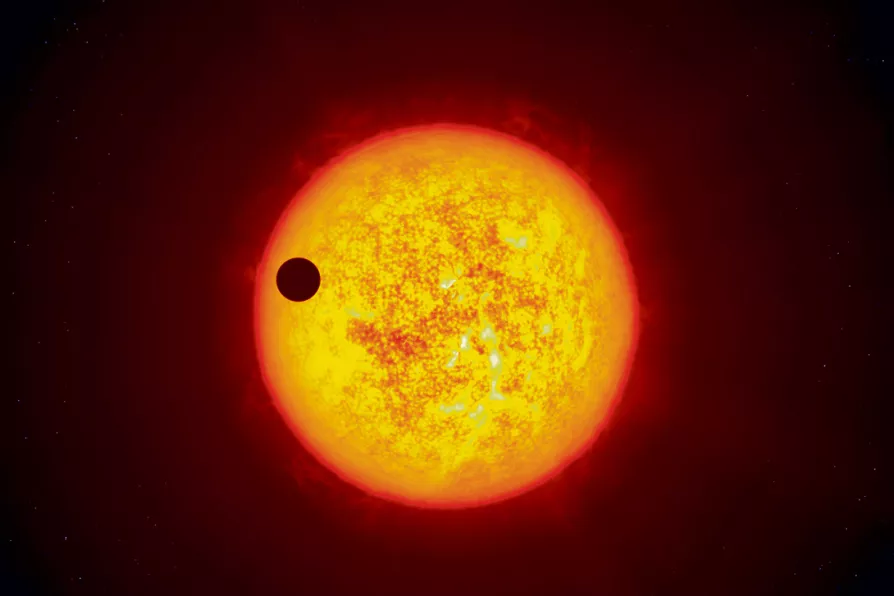

An artist’s impression of transiting exoplanet Corot-9b which is the first “normal” exoplanet that can be studied in great detail. It is the size of Jupiter and an orbit similar to that of Mercury. It orbits a star similar to the Sun 1,500 light-years away from Earth towards the constellation of Serpens (the Snake)

[ESO/L. Calcada/Creative Commons]

An artist’s impression of transiting exoplanet Corot-9b which is the first “normal” exoplanet that can be studied in great detail. It is the size of Jupiter and an orbit similar to that of Mercury. It orbits a star similar to the Sun 1,500 light-years away from Earth towards the constellation of Serpens (the Snake)

[ESO/L. Calcada/Creative Commons]

EXOPLANET research seeks to identify and characterise alien planets orbiting other stars.

Since the first exoplanet was confirmed in 1992, thousands of others have been found.

One focus for this research is the characterisation of their atmospheres. Our own atmosphere, the gas layer in which we live, is so intimately linked to the existence of life on Earth that understanding the atmospheres of exoplanets provides crucial evidence to identify other Earth-like planets.

JOHN GREEN’s palate is tickled by useful information leavened by amusing and unusual anecdotes, incidental gossip and scare stories

Neutrinos are so abundant that 400 trillion pass through your body every second. ROX MIDDLETON, LIAM SHAW and MIRIAM GAUNTLETT explain how scientists are seeking to know more about them

Science has always been mixed up with money and power, but as a decorative facade for megayachts, it risks leaving reality behind altogether, write ROX MIDDLETON, LIAM SHAW and MIRIAM GAUNTLETT