RITA DI SANTO draws attention to a new film that features Ken Loach and Jeremy Corbyn, and their personal experience of media misrepresentation

Lessons of individual development rather than collective or political consciousness

ANGUS REID reviews a book that is an important and comprehensive work of documentation

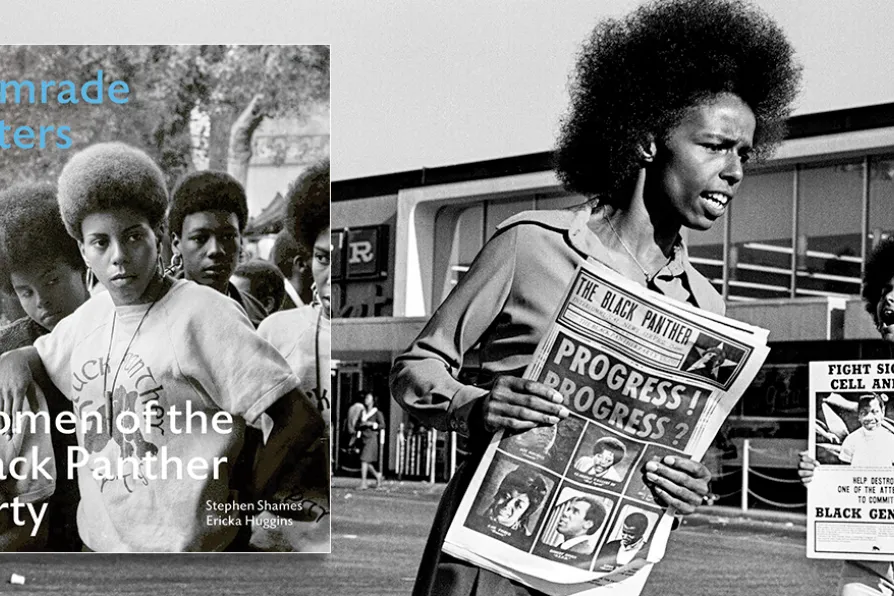

Gloria Abernethy sells the Black Panther newspaper while Tamara Lacey holds a sickle-cell anaemia poster at the Mayfair supermarket boycott in Oakland, California, 1971

[Stephen Shames]

Gloria Abernethy sells the Black Panther newspaper while Tamara Lacey holds a sickle-cell anaemia poster at the Mayfair supermarket boycott in Oakland, California, 1971

[Stephen Shames]

Comrade Sisters: Women of the Black Panther Party

Photographs by Stephen Shames, text by Ericka Huggins

ACC Art Books £35

IT IS impossible not to be moved by Stephen Shames’s innocent and spontaneous documentation of the communal “‘survival programmes” that were inspired by the Black Panther Party in the late 1960s and 1970s.

He was 20 years old, an amateur, and he found himself in the middle of a defiant and self-organising mass movement that was addressing existential problems in the black community in a way that was without precedent in the history of the US.

Suddenly, all of it is interesting.

Similar stories

MARIA DUARTE and ANGUS REID review Friendship, Four Letters of Love, Tin Soldier and The Ballad of Suzanne Cesaire

ANGUS REID calls for artists and curators to play their part with political and historical responsibility

RON JACOBS recommends a book filled with history and political theory that provides both a basis and inspiration to create a way forward

The Star's critic MARIA DUARTE reviews I Am Martin Parr, September Says, The Monkey, and The Gorge