RITA DI SANTO draws attention to a new film that features Ken Loach and Jeremy Corbyn, and their personal experience of media misrepresentation

Error message

An error occurred while searching, try again later.ANDY HEDGECOCK is intrigued by a scholarly account of how systemic disinformation can exacerbate the perception of threat and foster hatred

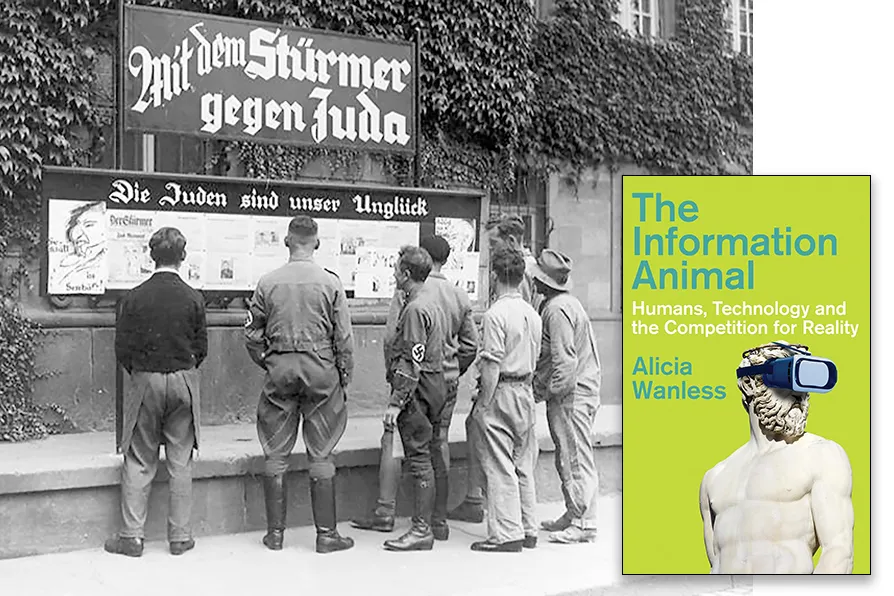

DISINFORMATION: Public reading of the anti-Semitic newspaper Der Stürmer, Worms, Germany, 1935 [Pic: German Federal Archives/CC]

DISINFORMATION: Public reading of the anti-Semitic newspaper Der Stürmer, Worms, Germany, 1935 [Pic: German Federal Archives/CC]

The Information Animal: Humans, Technology and the Competition for Reality

Alicia Wanless, Hurst, £27.50

“TECHNOLOGY can’t save us from ourselves,” says Alicia Wanless in this persuasive analysis of the relationship between people and their information environment.

Her key argument is that effective decision-making will require an interdisciplinary approach to the study of emerging information ecosystems, accompanied by a thorough understanding of human beings as “information animals.”

Wanless stresses our active role in constructing and transforming information and considers the sociopolitical context of disinformation. She makes the case for a research framework drawing on the success of earth science and ecology, disciplines which take a systems approach to understanding the physical environment. The discipline of “information ecology” will inform an understanding of the ways in which we interact with information, machines and other people.

Wanless suggests there is currently a tendency for policymakers to respond to challenges in the information environment — such as disinformation via social media — by focusing on content and the technologies used to distribute it. Content moderation and regulation are crude tools, she argues. Without knowledge of the experience and beliefs of those making sense of information, an attempt to block or modify its transmission could have unexpected or undesirable effects.

There is little point in attempting to tackle the threat of disinformation before we have a full grasp of the complex interaction of technologies, the agents using them and the outputs they produce. To achieve this, Wanless asserts, information ecologists need to draw on history, ethnography and linguistics as well as technology and information science.

To focus attention on the information environment as a whole — and to separate human information processing from information technologies — Wanless guides us through five conflict-based case studies.

Her consideration of power-shifts between cities in Ancient Greece highlights collision of information ecosystems based on competing sets of conditions and values. Political success, she concludes, depends on understanding the cultural and historical factors affecting one’s own ecosystem, and the ecosystems of others.

The chapter on the English civil war illustrates the risks of fixating on the means of communication and its outputs, while ignoring the intentions and capability of agents within the system. Charles I adopted a strategy of information warfare, blocking negative information and launching an influence campaign. If he had engaged more constructively with an increasingly literate population, he may have avoided defeat, loss of power and execution.

Wanless argues that rapid advances in telegraphy, and uneven improvements in literacy, facilitated a flood of sometimes superficial information in the America of the 1860s. This fuelled the violence that led to the outbreak of the civil war.

The information landscape of the years before the Vietnam war was considerably more complex: variables included the development of radio, the activities of exiled activists, the rise of international travel, connections to the French information ecosystem and two information “competitions” — one relating to Vietnamese independence, the other to the cold war.

The final study, Ukraine in 2014, focuses on the role of polluted and contested internet-enabled media.

This is a timely publication. As Wanless suggests, we are heading for a “polycrisis” in which global warming triggers migration, leading to the development of more diverse communities and ramping up economic uncertainty. Recent events in Britain and the US suggest that in this context, systemic disinformation is likely to exacerbate the perception of threat and foster hatred.

The strength of The Information Animal lies in Wanless’s sedulous scholarship and holistic approach to assessing the interaction of information, politics, society and psychology.

Its weakness is the author’s tendency towards longwindedness. Early chapters establishing the concept of information and justifying her use of the information environment framework are unnecessarily prolix. This is an important book, but one that deserves to be more accessible.