RITA DI SANTO draws attention to a new film that features Ken Loach and Jeremy Corbyn, and their personal experience of media misrepresentation

Error message

An error occurred while searching, try again later.CHRIS SEARLE relishes an account of the years when a black American music carried a message of anti-racism and class struggle

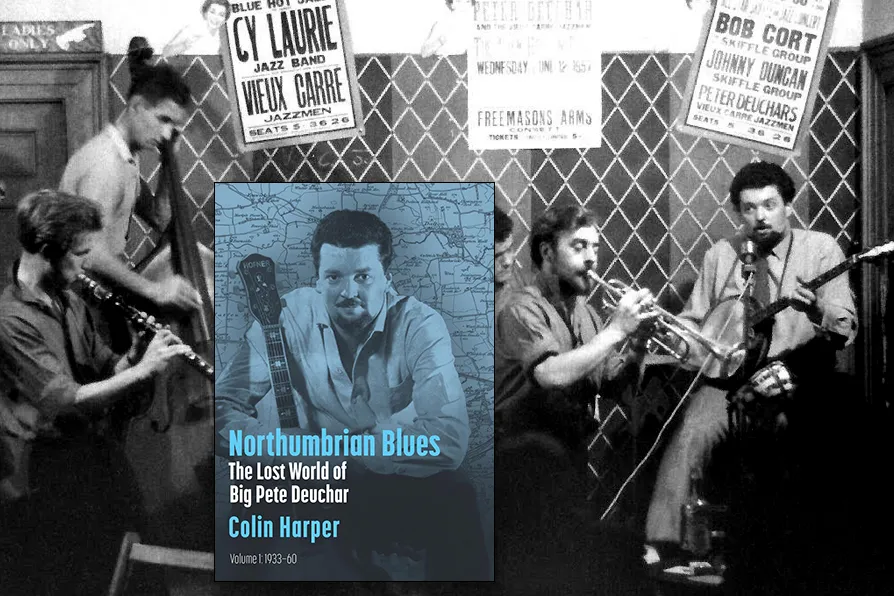

PIONEERING: Big Pete Deuchar plays The Vieux Carré [Pic: Courtesy of Pete Woodman]

PIONEERING: Big Pete Deuchar plays The Vieux Carré [Pic: Courtesy of Pete Woodman]

Northumbrian Blues: The Lost World of Big Pete Deuchar

Colin Harper, Jazz in Britain Publications, £13

WHEN this book arrived, I first of all flicked through the photographs of the protagonist and his cohorts from the early 1960s. There he was, snapped in 1961, playing banjo with Dick Charlesworth’s City Gents, a band I often used to hear at the St Louis Jazz Club, Elm Park Hotel, east London, as I worked in the cloakroom, hanging up the groovers’ donkey jackets and duffle coats.

My friend Spud’s dad ran the club, and I would get free entry for my cloakroom labours and handing out pass-outs to those who wanted interval drinks in the pub next door.

The early life of this banjoist is what holds this book together. “Big Pete” Deuchar was the grandson of a Newcastle brewery magnate who turned his back on his origins and dedicated his life to stimulating a thriving culture of New Orleans jazz in the city during the 1950s, when the imitated sound of the Crescent City could be heard in urban venues right across Britain.

Colin Harper’s book is more than a sparky musical biography: it is an invaluable piece of social and cultural history of a post-war era when live “traditional jazz” crowded into teenage hearts and consciousnesses in its own very British way, led by the music of the “Guv’nor” Ken Colyer, recently returned from a sojourn in New Orleans, who transplanted its jazz into pub rooms and often dingy venues from Glasgow to Bristol, and Nottingham to Elm Park.

Deuchar was an early Colyer disciple who was determined to make Newcastle swing with the music of Bourbon Street, and he established his Vieux Carre Jazzmen in what the Newcastle Evening Chronicle described as the “dark, dirty, dangerous” fully licensed ex-Labour club in Melbourne Street, Newcastle 1.

But although Deuchar’s early life in music is the book’s narrative thread, and it is much more the chronicle of a time of youth discovery and insubordination. Colyer and his band led the hugely supported protest marches to the Atomic Weapons Research installation at Aldermaston, Berkshire, and the music he fervently embraced was that of an oppressed black and creole community still living under racist Jim Crow laws in Louisiana.

In England, to love the music was to hate racism, and the visits of the veteran ex-docker New Orleans clarinetist George Lewis to play with the Colyer band, and those of blues musicians like Big Bill Broonzy, Sonny Terry, Brownie McGhee, Little Brother Montgomery, Memphis Slim, Howlin’ Wolf, Muddy Waters and Jesse Fuller (who I remember well singing the blues in Elm Park) were evidence of a younger generation moving away from the Teddy Boy licks of Bill Haley, to a black American music which carried a vital message of anti-racism and struggle.

The records they made with British musicians are still there to bear witness and are well worth searching out.

There’s an excellent chapter of Deuchar’s 1957 stay in New Orleans, where he played (but not on public platforms — still disallowed by quasi-apartheid laws) with virtuosi like clarinetist Alphonse Picou and trumpeter Kid Thomas Valentine; and another on the Lewis band’s 1959 Britain visit, where the veterans were welcomed by enthusiastic crowds at Liverpool Docks and Kenny Ball’s Band (who were stopped in mid-chorus by an aggressive police presence), and given momentous plaudits in concert venues across the nation, including Manchester, Southampton, Leicester, Bristol, Glasgow, Birmingham, London and of course Newcastle City Hall.

As the Melody Maker reporter put it: “George Lewis received the most fantastic jazz welcome ever when he arrived at London’s Euston Station on Sunday: and then he retired to bed!” All this was jazz against racism at its most dedicated and explicit.

Such was the ambiance of 70 years ago, powerfully described in Harper’s book, which in its own way is an inspiration for now-times. But play the music while you’re reading it!