RITA DI SANTO draws attention to a new film that features Ken Loach and Jeremy Corbyn, and their personal experience of media misrepresentation

Error message

An error occurred while searching, try again later.TONY CONWAY welcomes a thrilling and concise history of Hope not Hate, that is also a manual full of tactical advice

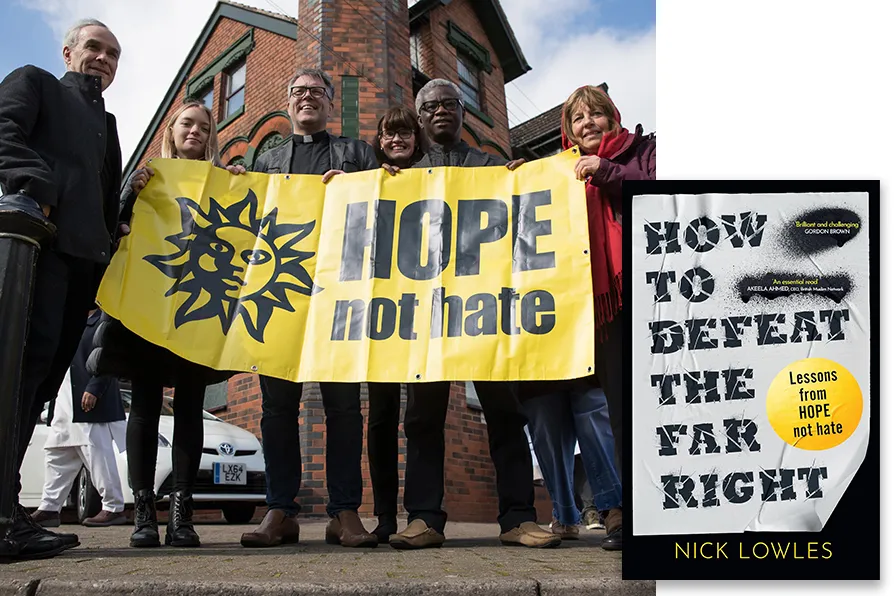

THE GOOD FIGHT: A Hope not hate banner outside the Slade Road Mosque, Birmingham before Friday prayers where police responded to reports of smashed windows after five mosques were attacked. March 2019

THE GOOD FIGHT: A Hope not hate banner outside the Slade Road Mosque, Birmingham before Friday prayers where police responded to reports of smashed windows after five mosques were attacked. March 2019

How to Defeat the Far Right: Extremism is on the rise – HOPE Not Hate can stop it

Nick Lowles, Harpernorth, £10.99

IN 2010 I remember waking up and eagerly tuning the radio to see what the result of the Dagenham and Barking council election was. This was at the height of the fascist BNP power grab. They expected to do well. They didn’t succeed and were put on the back foot, probably never recovering. Whilst many anti-racist groups were included, the anti-racist anti-fascist group Hope Not Hate should take a lot of credit. I had a spring in my step that day. We could win!

Nick Lowles’s book, produced this year, is almost a history of Hope Not Hate, from its origins in Searchlight over 20 years ago, to a campaigning organisation. Searchlight had many great editors and contributors including the author himself. As a young Birmingham trade unionist I often came across Maurice Ludmer when he was president of Birmingham Trades Council.

Searchlight had a history of undercover work infiltrating fascist bodies, and Hope not Hate has continued to do this. In fact, the first chapter details how an online group made up of young men was infiltrated, with the highlighted protagonist being arrested, but then stating clearly that this intervention saved his life. The alternative to Hope in this instance would have resulted in more online hate and street thuggery.

At some 300 pages this book isn’t long, but it is detailed, covering a range of case studies. It doesn’t shy away from self-criticism and criticism of other anti-fascist groups.

Additionally, I know that a number of people on the left are highly critical of Hope Not Hate’s undermining of the Corbyn leadership for being supposedly anti-semitic. It is the case that Hope Not Hate does not back away from calling out all hateful acts, including those perpetrated by extreme Islamists, but the author does highlight the Corbyn-led campaign in 2017 as being full of hope, as distinct from the negative campaign of May’s Tories.

Also, it quite rightly calls out grooming gangs; an issue the government is still struggling with as I write.

The author highlights a number of anti-fascist campaigns, particularly against the BNP and more recently against Ukip. It identifies a number of those whom he calls local heroes, whom I won’t name for fear of missing someone out.

Lowles does identify the absolute necessity of developing local campaigns with local leaders. He writes: “Our early community resilience work was done in direct response to threats we faced… A few years later, however, we would try to construct a framework for how we approached these things… and share that approach.”

In 2019 a Hopeful Towns Project was created. This was all about community cohesion. A report, Understanding Community Resilience In Our Towns, was produced, categorising towns into 13 different groups. This report is worth reading and emphasised the importance of a place-based approach.

Lowles covers too much ground for it all to be highlighted. However, worth mentioning is the work with the Daily Mirror celebrating Modern Britain which touched people in Dudley when the Hope Not Hate battle bus turned up. It also identifies the rise, and fall, and rise again of Farage: Farage’s Reform UK has learnt from some of the errors of Ukip but the anti-migrant message still comes through – in Ukip he was anti-eastern European, defining people from Poland and elsewhere as the main threat to British life.

There is also extensive analysis of Farage’s link to Trump and the network of right-wing commentators including Sir Paul Marshall, the co-owner of GB News and the founder of Unherd. In 2024 a Hope Note Hate researcher identified that Marshall had a following on X for his racist Islamophobic and homophobic views. This research shows the importance of obtaining knowledge of the community that anti-racists are operating in, and in identifying the main protagonists on the far right. Protagonists such as Marshall would prefer to operate unnoticed. Lowles gives examples throughout the book as to how this information was obtained.

There are fascinating insights into anti-Muslim hatred, fostered by the so-called anti-jihad movement. The narrative, most recently highlighted by Jenrick in his comments on the Handsworth area of Birmingham, has now crossed into the mainstream. The author also highlights the activities of the BJP in Leicester, and those of Hindutva, a modern ethno-nationalist movement. This is an area that anti-fascists would do well to study, given the growth of support for Reform UK amongst the Indian community.

In the final chapters instances are given on how we can take the challenge to Reform UK through democratic popularism in areas controlled by Reform UK: against sewerage overflows, for example.

Lowles ends by making a call for progressive groups to work together with anti-poverty campaigners, asylum groups, climate groups and those working for greater democracy. Over the last few days I’ve heard of examples of such groups in Hull through the local trade union council, and in Thanet by the local anti-racist group which is now campaigning on NHS services.

In conclusion, much of the book covers local activity, undercover investigations, and the links to be made internationally. As Lowles says we must work together this must apply across unions and nationally.